Seeking The Janus Principal

Leadership and School Improvement

There would seem to be a general consensus that the two most important factors driving student performance in schools are firstly, the quality of classroom teaching, and secondly, the quality of school leadership.

It is therefore understandable that the majority of articles that discuss school improvement seem to focus on, and offer suggestions for, the development of leadership skills in school principals, for it is clear that that first factor, quality teaching, has a significant correlation with quality leadership.

In a good deal of this discussion, authors tend to place their emphasis on the primary responsibility of the school principal being the agent for the generation of a culture of vibrant and enthusiastic learning within the school.

In turn there will be an emphasis on the school principal cultivating positive relationships in every dimension of the life of the school community – with staff, students, parents and wider school community.

And many writers have offered, on the basis of evidence for improving outcomes for students from year to year, strong and persuasive claims for the effectiveness of such exhortation. One model for effective principal leadership gaining increasing support has been the adoption of the ideal of Invitational Education, the cultivation of positive enthusiasm by staff and students for learning driven by the embedding within the school community core values of Care, Optimism, Respect and Trust.

Claims for the effectiveness of this leadership model have been reinforced by a commitment to the gathering and interrogation of data showing alignment of the model with improvement in student performance, measured against national and international standards.

However, and notwithstanding the value of this discussion and debate about the leadership role of principals within a school, there is a significant area in which the need for leadership by principals is too often overlooked.

Leading Within a System

All schools are part of a system of education within a political entity called the state. The state’s role in regulation, policy formulation and funding of school education, whether or not the school is directly under the control of a ministry of the state, necessarily shapes the context in which school improvement is pursued by school leaders.

Any system, arising as it does within a political context, will inevitably carry with it ideological pressures – and beyond ideological pressures, the reality that the efforts of the school leader to provide quality outcomes in student achievement must be made within a framework of system demands and requirements that can compromise those outcomes.

Principals are best placed to understand and assess the tensions between pursuit of high levels of student achievement within a school and the sometimes constraining demands of the system, whether those constraints arise because of unchallenged ideological assumptions, or because of misalignment of policy with what principals know actually works in the classroom.

Sometimes systems impose pedagogic methodologies that clearly run counter to the actual work of teaching within a school. A clear example of a methodological theory of educational practice imposed by a system that constrained rather than assisted school improvement was the theory of Outcomes Based Education adopted by the Western Australian Department of Education in the early 2000s.

Principals and teachers were well aware that the administrative burdens created by modes of assessment of student achievement associated with OBE detracted from the ability of schools to create vibrant leaning environments.

The consequences of the adoption of this educational theory were foreseen by many working as both leaders and teachers in schools – but there was insufficient organised resistance to prevent its adoption.

Within five years however, the limitations of OBE and its impact on the actual work of learning in schools had become clear enough, and the State abandoned the methodology. Meanwhile, an entire cohort of Year 8 to Year 12 students had perhaps a less productive period of senior school learning than might otherwise have been the case.

In that case, the ideological imposition was generated at the State level within a federal system of government which also assigned regulatory and system design roles to a Federal ministry.

And at this national level of the state, in two key areas, initial teacher education and training, and curriculum, system limitations and edicts failed to reverse both a decline in the overall quality of entrants to the teaching profession, and poor curriculum design driven by demand for increasing subject area coverage with an associated narrowing of scope in disciplines such as history.

In the face of such powerful and shaping influences on the work of schools, efforts by principals to drive school improvement become complicated, and more difficult than they might otherwise be.

Responding to the System

Now it is clear that no one principal can effectively intervene to mitigate system wide demands.

But principal associations have been less effective than they might have been in influencing system wide issues.

In part, this has been because of a propensity for associations at the State level, in the Australian federal system, to concentrate on issues of resourcing, rather than system design and the alignment of the system with the development of vibrant and successful learning communities. And this propensity is understandable, given that the associations exist primarily to represent the views of their members to the controlling, State-based Department and Ministry of Education, and that on the whole, association members will usually have at front of mind questions of school resourcing and staff management.

But the solutions to these more immediate pressures tend not to address issues of system structural design and policy parameters which actually have profound impacts on successful outcomes for students. In terms of investment by the state in school systems in Australia over the past two decades, at both the individual State and Federal level, dollars per student have increased, so it is not a matter of a dwindling of base resourcing – quite the opposite.

Yet it is clear that notwithstanding the commitment and talent of many school leaders, at some level, Australian schools have been less than wholly successful in translating student engagement into high levels of achievement.

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) of the OECD publishes every three years a table of the standing of education systems across the world in terms of the assessed capability of students at age fifteen in numeracy, literacy and science skills. Relative to other OECD jurisdictions, the performance of Australian students has been in decline over those two decades. More telling is the fact that:

“Our own performance is regressing. The average Australian student is more than one full year behind 2003 levels in maths, one full year behind 2006 levels in science and a full year behind 2000 levels in reading.” (1)

The dominance over recent decades of inquiry-based systems of learning, and teaching practice associated with that model of pedagogy has been challenged in recent times by significant accumulation of evidence that explicit instruction can deliver better outcomes in terms of student learning. (2)

There is an increasing weight of evidence for the need to ensure that schools and their leaders adopt an evidence-based system of pedagogy that overturns theories of pedagogy still current in the teacher training syllabi of many of Australia’s tertiary institutions.

There is however little evidence for the voice of the principal class as a participant in this crucial contest in educational theory.

In part, this flows from the reality of the principal’s immersion, quite properly, in the demanding task of providing the leadership required in each and every school to maintain not merely positive and orderly administration of school activities, but the crucially important generation of engagement by the whole school community – staff, students and their parents – in the excitement and satisfaction of learning and the growth of knowledge.

The Janus Principal

There exists however a need for principals to be not only highly aware of where education policy underpinning the system in which he or she operates mitigates against the achievement of high quality outcomes for students, but also actively engaged in dialogue with the custodians of the system at the state level to shape and influence that policy.

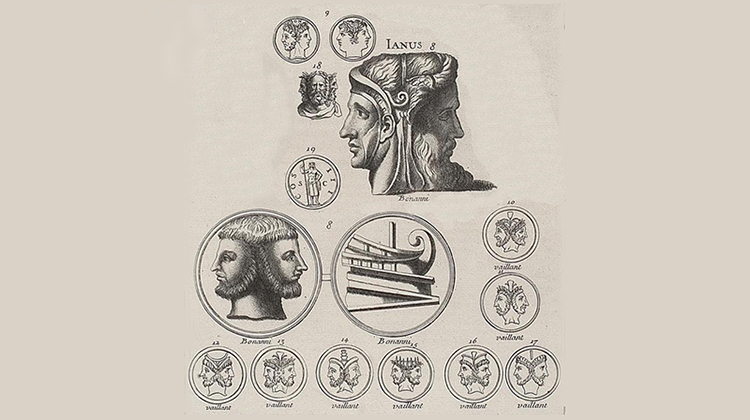

The Romans had, amongst a plethora of Gods to be invoked for success, and propitiated to ensure that success, one with a particular prominence in relation to both the home and the state. This God was Janus, the God of gateways and beginnings. We still acknowledge him in the name of the first month of the year. He was a God of transitions. And school education is perhaps the most significant transition humans make between early childhood and early adulthood.

He was represented as a God by a statue with two faces. In one sense those faces marked the passage of time, one looking back to the past, the other forward to the future – in this aspect he was the God of Beginnings. But the faces also signified the transition from the private world of the home to the larger world of Roman society, which was why the two-faced God was often to be found as a statue on the threshold of a Roman villa.

What relation does this ancient figure have to my theme? Simply that principals must have some sense of this God as an important tutelary deity with respect to the role the principal has in the world of education today.

One face is turned toward the particular school community for which the principal has accepted the responsibility and the duties of leadership.

But there is another realm of responsibility and duty to which the other face must be turned, and that is to the larger policies of the state (and in the Australian context, the State in both its local form and its Federal form, as education policy is made in both dimensions) which impact upon the school community he or she leads.

In the end, principals are best placed to understand where tensions between system policy settings and classroom practice may undermine what all of us would want to see – high levels of student achievement.

But work must be undertaken by principals to ensure their understanding of limitations in system policy and design is considered by the state and can positively influence policy and system change where that becomes desirable.

Collegial and Collective Action

This is, in a real sense ‘political’ work – and, like most political work it will be largely done through organisations, rather than by single individuals.

I am not aware that any of the professional associations of principals in Australia are constituted in ways that that would mobilise the experience of their members to specifically generate and propose education policy.

While good work is done in representing the views of principals working within the given parameters of the system to the custodians of those systems, there seems to be little to be heard from their Associations on larger questions of education policy – what should we be teaching (curriculum) , how should we be teaching (what are the most effective pedagogical methods), how do we assess whether our teaching is effective (data gathering, testing, and interpretation) and are we providing future generations of students with the best and most effective teachers (initial teacher training and professional standards).

Perhaps one way to ensure that there comes into existence a powerful and influential voice for school leaders in the crucial debates on system design, and system policies, would be for principals to encourage the formation, within their professional associations, of a specific sub-committee tasked with review, debate and subsequent formation of a platform on educational policy questions.

The adoption of such a strategy would bring focus to the role principals and their associations can play in shaping future educational policy. Currently, or at least it seems so to me, engagement in this sphere of policy formulation and design, if it occurs at all, is ad hoc and desultory.

Yet, as I have argued, principals do have a responsibility to engage in the process of formulation and design of educational policy. It is they, and their schools, and most importantly, their students, who bear the brunt of the imposition of policies across the education system which are inimical to the development of school communities vibrantly, and successfully, engaged in the adventure of learning.

This is, undeniably, a further demand on the intellectual resources of the school leader, likely already extended by the daily pressures, both intellectual and emotional, of that role. To contribute positively to debate on such large questions as the system of initial teacher training and desirable reform, or the adoption of rigorously based pedagogical practice to displace long-established ideas such as Learning Styles designed instruction, the Janus principal must accept the burden of remaining intimately engaged with and by both the academic and the political debates which swirl around and through the world of school education. It is a lot to ask.

In seeking the Janus principal, however, we are seeking to strengthen the voice of both lived pedagogical experience and complex administrative experience within large systems. We entrust the future of our children, and ultimately, the nature of the society in which we live, to their teachers and those who lead them.

We should be eager to temper the influence of politicians and non-practitioner academics on system design and policy for school education with that voice, because it is the voice with the most direct and immediate insight into the quality of alignment between system demands and the student outcomes achievable within each and every school.

It is my hope that there will be principals willing to take up the challenge of creating that stronger voice by working within their professional associations to create, built on a foundation of shared values and shared knowledge, an acknowledged and respected source of advice and guidance to the state, and the community, on better education policy and fit-for-purpose system design.

Cliff Gillam holds Masters degrees from the University of Western Australia (UWA) and Monash University, and spent the first eight years of his professional life lecturing at UWA in English literature.

After a further eight years working as a theatre professional, he commenced a career in public service, retiring as a senior executive in 2017. He was for 8 years the Executive Director Workforce in the Western Australian Department of Education, and assisted in the implementation of the Independent Public Schools reform commenced in 2010.

Post-retirement, he has presented senior leadership programs for the Department of Education, provided consultancy services to the Principals' Federation of Western Australia, and developed a program in the History of Ethics delivered at the Albany Summer School.

i Cited by Paul Kelly, The Weekend Australian, July 24-25, 2021 p.16

ii Cf Cognitive load theory (nsw.gov.au)