Micro-talk and Micro-moments: Building Presence for School Leaders and Teachers

The challenge for school leaders and teachers is to establish an educational presence in the school community and classrooms. While leaders’ keynote speeches and strategic policy proclamations have their place in the establishment of credibility and trust, the key, determining factor is the much-overlooked practice of micro-talk. In this paper we examine this often-ignored phenomenon and its importance in establishing leaders’ and teachers’ presence, autonomy, and agency in schools and the school community.

Micro-talk now has a name, and Mark Travers (2023) explained micro-talk as: ‘It’s the nod as you cross paths with a colleague, the swift “Hi” to a neighbour, the heart emoji reaction to a friend’s Instagram story, the “Thanks” to the server at the cafe or the “Good” in response to a casual inquiry about your day.’ The thousands of uncounted micro-talk exchanges must include the social media reactions, body language and gestures, the impact on perceptions of self, identity, agency, autonomy, and presence; and so, they cannot be ignored in a social environment like education.

Growing Positive Relationships Through Micro-moments

Relationships underwrite trust, and micro-talk is very important in acknowledging every individual in a social environment. Standing at the school gate and greeting parents and students each morning with a few words and a smile reasserts the relationships between the participants, breaking down barriers that can develop. The ability to insert a student’s or parent’s name to the dialogue, adds to the strength of the relationship account credit balance.

In the modern educational context, school principals’ and teachers’ conversations are frenetic as they flit around the schools and classrooms attending to issues that must be resolved quickly. Time and workloads are now key stressors. In the early research by Harry Wolcott (1973/2003, p. 89) of the principal Ed Bell’s “average day,” he found that the principal was alone (working) in his office for only 15% of the day, and the rest of the day he was engaged in planned and unplanned meetings, telephoning, walking to meetings, and talking on the intercom. Pulling apart this data (p. 91), it was shown that the Ed spent 35% of his day listening to others, and 36% of the day talking to others. In this modern era. As Brett Henebery, (2023a, 2023b) noted, the worlds of school teachers and leaders have now changed.

The types of conversations in schools are dependent on the levels of cultural development and the operational stability in the school or the classrooms. In established schools and classrooms that are operating well, the “big picture” issues are established, and conversations address the smaller, incidental and fine-tuning issues. These micro-exchanges embedded in micro-moments are a factor of the school’s culturally embedded cohesion, and they can affect the school leaders’ ability to do deep work (Boyd & MacNeill, 2020).

The Power of Greetings

Travers (2023) noted that mastering micro-talk was a way forward to establishing more profound conversations. As a result of COVID, society changed and the phenomenon of “minimal social interactions” has been shown to be an important factor in subjective well-being (Ascigil et al. 2023, p. 1). These authors (Ascigil et al. 2023) thought the advantage for some people of a simple “Hello” or “Thank you” was there was less chance of rejection, or not knowing what to say, than in a deep conversation.

Bob Yirka (2023) noted that the World Health Organization observed that loneliness, related to isolation, was a major mental health concern, and consequential research showed that: interacting with strangers on a regular basis can lead to feelings of belonging to a community, which can make people feel more accepted and even valued by those who share their small part of the world,” which reduces their sense of loneliness.

Presence, Voice, Identity, and Agency

The subjective experience that “I” am the one who is causing an action, referred to as the sense of agency is fundamental to the sense of self (Ohata et al. 2022). “Voice”, in the social-psychological sense has become a concept that represents a confluence of personal agency and identity, which are projected into a social environment s presence. The reflectant responses from the community then inform the individual’s beliefs about self, identity and agency. The concept of voice includes all communication types- words (spoken and written), gestures, body language, and even silence or ignore, which other senses register and evaluate. Also, every actor is aware that the sound and tone of a speaker’s voice colours the intent of verbal communication. Jacquemont (2021) made the point that voice is an important part of a person’s self-identity.

Amy Cuddy (2016, p. 52 et seq.) equated growing presence to “expressing your authentic best self,” and an important note that she makes is about personal accessibility (p. 53). So, while school leaders standing at the school gate and circulating during recess time is often dismissed as an important leadership characteristic, it is useful to remember that relationships underwrite credibility, trust and presence.

In a neat figure, Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan (2021, p. 101) show the inter-linking connection between a heart-shaped label of “agency” that concatenates to identity, to belonging, to mastery and then to efficacy. While this diagram was designed to examine students’ agency, it holds good for adult agency and learning.

Micro-Gestures

A complementary aspect of micro-talk is micro-gestures. A verbal “No” response to a question is often qualified by a facial expression, body language, or a gesture, which allows the listener to determine the strength of the negative response. We will include smiling as a body language/gesture because it adds a dimension to the expressed verbal communication. So, the words, “Good morning. How are you today?” uttered with a smile is a signal of acceptance and respect for the listener,

Body language experts, and even police interrogators look for the small body language actions that indicate the truth of the statements being tendered. In the time of contested political elections these forensic analysts study what is being said by aspirant Presidential candidates, and pass judgments about the intent of the statements.

Action Research: Presence at the School Gate and Beyond

To examine the value of micro-talk and micro-gestures in cultivating leadership presence, one of the authors undertook an action research process grounded in his routine morning interactions at school. Between 8:15am and 9:00am, a colleague observed and documented all interactions he had with students, families, and staff. This period included 15 minutes of gate duty, 15 minutes of pre-bell classroom visits, and 15 minutes of interaction during the initial phase of classroom instruction.

From 8:15am to 8:30am, he was stationed at the front gate, greeting families and supervising arrivals. During this time, he engaged in short conversations with 55 individuals, parents, staff, and students. The conversations did not exceed one minute and included a spectrum of relational exchanges from a simple “Hello” or “Good morning” to comments about a child’s new bike, a parent’s recent holiday, or questions about a child’s wellbeing. Importantly, he greeted every child who entered the school by name, adding another 85 interactions to his morning. These small acknowledgments were more than pleasantries, they were affirmations of identity, acts of inclusion, and relational deposits into the school’s social bank.

From 8:30am to 8:45am, he moved through classrooms and shared learning spaces, engaging with teachers, education assistants, cleaning staff, and an additional 75 students as they prepared for the day. These micro-moments included everything from gratitude expressed to a cleaner, to a check-in with a teacher, to a reassuring word to a nervous student. These were moments of visibility and care, reinforcing that leadership is not confined to meetings or strategy, but lived out in everyday interactions.

Between 8:45am and 9:00am, he remained in classrooms as instruction began, continuing to interact with students and staff in ways that supported both relational and learning-focused purposes. This transition from relational to instructional presence demonstrated the fluidity of leadership voice and agency in educational settings.

In total, more than 200 interactions were documented in this 45-minute period. Each one, however small, carried weight. This observation aligns with Harry Wolcott’s seminal ethnographic study of Principal Ed Bell (1973/2003), which revealed that Bell was alone in his office for only 15% of the day. The remaining 85% was spent in meetings, walking between engagements, speaking on the intercom, and, most strikingly, talking with and listening to others. Wolcott’s breakdown of Bell’s daily activity showed that 35% of his time was spent listening, and 36% talking. More than fifty years on, my own morning routine echoes this dynamic. Despite new pressures of modern schooling, administrative overload, accountability metrics, and digital distractions, the human rhythms of school leadership remain much the same.

What has changed, however, is our language and awareness. The term micro-talk now allows us to name and validate those fleeting but powerful interactions that animate a leader’s presence. As Travers (2023) explained, micro-talk includes not just spoken words, but gestures, body language, and digital expressions. These build trust, credibility, and connection. Similarly, Cuddy’s (2016) notion of presence as “expressing your authentic best self” reminds us that these micro-moments are not ancillary, they are leadership in action.

This case reaffirms a central argument of this paper, that being that in the ecology of a school, presence is built through relational repetition. The consistency of showing up personally with intention, through eye contact and smile cements leadership into the fabric of the school. These micro-moments are not minor. They are the hidden architecture of culture, trust, and collective identity.

Conclusion: Micro-Talk, Macro Impact

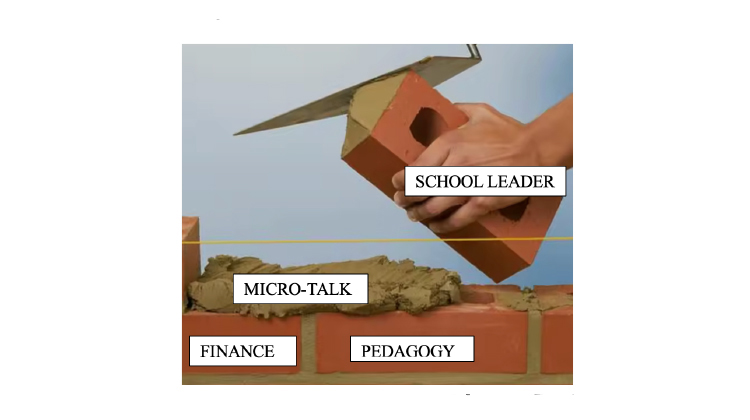

In the fast-paced, often complex world of contemporary schooling, it is easy to overlook the power of the small interactions. Yet, in this paper we have argued that micro-talk and micro-gestures, those brief, often unconscious acts of communication, are not only foundational to school culture, but central to a leader’s presence, agency, and relational capital. Whether at the school gate, in the playground, or among classroom conversations, these micro-moments act as connective tissue that binds communities together. They cultivate trust, signal care, and reinforce identity. As seen through the lens of action research, even a single morning can reveal the profound effects of intentional, authentic, and consistent interactions. Leadership in schools is not just about strategic vision, rather it is about being present in the moments that matter, again and again. Micro by micro, these interactions cement the wall of trust on which schools and their communities stand.

References

Ascigil, E., Gunaydi, G., Selcuk, E., Sandstrom, G.M., & Aydin, E. (2023). Minimal social interactions and life satisfaction: The role of greeting, thanking, and conversing. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/19485506231209793 journals.sagepub.com/home/spp

Boyd, R., & MacNeill, N. (2020, September). Deep work: Sunk on the treacherous shoals of time control in tough schools. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/Deep-Work-5065

Cuddy, A. (2016). Presence: Bringing your boldest self to your biggest challenges. Orion Publishing Group.

Henebery, B. (2023a, March 21). 60-hour weeks and sleepless nights – Why Australia’s principals are leaving in droves. The Educator. https://www.theeducatoronline.com/k12/news/60hour-weeks-and-sleepless-nights--why-australias-principals-are-leaving-in-droves/282189

Henebery, B. (2023b, March 30). A day in the life of an Australian school principal. The Educator. https://www.theeducatoronline.com/k12/news/a-day-in-the-life-of-an-australian-school-principal/282241

Jacquemont, G. (2021). A change to the sound of the voice can change your very self-identity. Scientific American Mind, 33(1), 16. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0122-16

Ohata, R., Asai, T., Imaizumi, S., Imamizu, H. (202). I hear my voice; therefore I spoke: The sense of agency over speech is enhanced by hearing one’s own voice. Psychological Science, 33(8) 1226–1239. doi:10.1177/09567976211068880www.psychologicalscience.org/PS

Safir, S., & Gugan, J. (2021). Street data: The next generation model for equity, pedagogy and school transformation, Corwin. Travers, M. (2023). How to master the new art of micro talk. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/traversmark/2023/09/27/how-to-master-the-new-art-of-micro-talk/

Wolcott, H.F. (2003). The man in the principal’s office: An ethnography (Updated edition). Altamira Press. (Original work published 1973).