Mattering: Resurrecting this Understated Concept in School Practices

The late Reverend Desmond Tutu said: ‘We say, “a person is a person through other people”. It is not ‘”I think therefore I am”. It says rather: “I am human because I belong” I participate, I share. A person with ubuntu is open and available to others….’ (Tutu, 1999, No Future without forgiveness, p. 35)

A neglected aspect of social and professional development in schools is the concept of mattering. In life, most people need the reflectent, social acknowledgement of mattering because humans are social beings who need to belong and be recognised. In their original research Rosenberg and McCullough (1981) identified three inter-related components of mattering:

‘(1) the sense that other people depend on us; (2) the perception that other people regard us as important; and (3) the realization that other people are actively paying attention to us. They suggested that being a focus of attention is the most central mattering component. Rosenberg (1985) expanded on this conceptualization by suggesting that mattering also includes the notion that other people would miss us if we were no longer around’ (Flett, 2022).

It is interesting that of the two sides of this concept - mattering and self-esteem, self-esteem became topical; and mattering, which underwrites self-esteem has been largely ignored, until now.

Mattering is important in a personal context, an organisational context, and in society. The consequences of the failure of mattering can be alienation. For example, in the contested context of American society, Roderick Carey (2019, p. 371) defined mattering as:

‘Often articulated in contemporary social movement discourses in relationship to lives of Black boys and men, mattering is a social-psychological concept concerned with the ways an individual develops thoughts and feelings that direct behaviors given the influences of the presence (actual or imagined) of others in society.’

Carey, Polanco and Blackman (2022) examined Carey’s The Black Boy Mattering Project conducted with high school aged students, and they reported:

‘Our data from the project reveals that interpersonal relationships and perceptions drawn from societal messaging impacted boys’ perceived mattering, and thus their self concepts. While the boys shared ample experiences with marginal mattering and perceived that they only mattered partially for athletics and entertainment in society, and sometimes to teachers and peers in schools, there were positive encounters that made them infer mattering’ (p. 76).

In a developmental sense, most people can report on their personal perception of the strength of a relationship, and we are all aware of what happens when the strength of a relationship is uneven. It was helpful that Carey, Polanco and Blackman (2022, pp. 74-75) proposed three levels of mattering:

- Marginal mattering

- Partial mattering

- Comprehensive mattering

Perceptive students, even in primary school, can soon work out where they fit in this mattering hierarchy, and it is widely acknowledged that in the modern era that the quality of teaching and learning is dependent on the strengths of the personal and professional relationships.

Mattering and Youth Education

Some years ago, the senior author of this article was the principal of primary school in a remote Indigenous community, and at the school’s recess time when the prison truck that was transporting Indigenous prisoners to daily community work-tasks went past, everyone waved, and the prisoners waved back. “There is my brother.” “There’s my cousins.” All of the students all knew the mainly teenaged prisoners, and there was no shame, because being jailed was almost a rite of passage for these young men who had never finished high school. These former students had just slipped through the system, and nothing was done - it didn’t seem to matter.

Carey (2019, p. 370) summed up this dismal situation rather well.

‘… due to neoliberal reforms and stakeholders’ structural incapacities to imagine and do otherwise, educators fail to construct contexts in which Black boys and young men can robustly infer their comprehensive mattering. Thus, educators and researchers miss relational opportunities to support Black boys and young men in imagining alternative lives that compel their fullness of interests, latent talents, and subsequent worth.’

In a recently released book, It Takes an Ecosystem, the authors, Akiva & Robinson (2022), strongly supported Carey’s stance, and argued that the unethical inequity matter of failing youth education is problematic at personal, moral and societal levels, and this signals to youths that they do not matter. The moment that schools and parents fail to address school attendance it signals to the non-attenders that they do not matter. The issue is so important that a multi-agency approach is needed to address the issue, coupled with a rethinking of educational programs because normatively/comparatively reported educational success labels these students as failures every day they attend school.

Alienation, Gangs, Cults and Mattering in a Negative Sense

Alienation is a social-psychological phenomenon in which a person becomes estranged, in terms of mattering in a positive sense, from other people, and Rachel Barclay (2018) identified six common types of alienation, all of which influence mattering. (See Table 1, below).

Table 1 Six Common Types of Alienation.

| Type | Definition |

| cultural estrangement | feeling removed from established values |

| isolation | having a sense of loneliness or exclusion, such as being a minority in a group |

| meaninglessness | being unable to see meaning in actions, relationships, or world affairs, or having a sense that life has no purpose |

| normlessness | feeling disconnected from social conventions, or engaging in deviant behaviour |

| powerlessness | believing that actions have no effect on outcomes, or that you have no control over your life |

| self-estrangement | being out of touch with yourself in different ways, mostly being unable to form your own identity |

Estrangement and exclusion are interesting, and Isaac and Ora Prilleltensky (2021) confirmed what most people know:

‘Has anyone excluded you from a group? If not, you’re lucky, but if such things have happened, you know these experiences hurt. They hurt because they threaten your sense of mattering; and if they happen often enough, research shows, they shatter your psychological and physical well-being. Indeed, the experience of exclusion has been linked to serious consequences, ranging from stress and depression to suicide to mass killings. In some instances, as in the case of Christian Picciolini, who became a skinhead to find acceptance, marginalization leads to joining extremist groups’ (p. 12).

It is noted that young people desiring mattering status, and acceptance, find joining gangs exciting, particularly when they are from poverty-stricken backgrounds with the lack of a support network:

‘It is very possible that these juveniles are looking for a surrogate family. These teens joining are obviously lacking understanding, affection, and affirmation in their households. It is likely these youths feel highly neglected and alienated where they are supposed to feel the most comfortable. When needs for love are not met, these young people are apt to join these gangs to feel involved’ (UKEssays, 2018).

Forrest Stuart (2020) in his ethnography (Ballad of the Bullet) made the point that many gang recruitments are through familial connections. For example, Dominik, who looked forward to joining the Black Counts gang in Chicago when he was older, was inducted as a child by family members into Black Counts’ handshakes and lore:

‘Reflecting a sense of inevitability, Dominik explained that he “just fell in line”. Becoming a Count was something all the men in his family “just did”. Like the rest of the Corner Boys, Dominik’s Black Counts family members proudly initiated, or “blessed” him into the gang at age thirteen’ (Stuart, 2020, p. 24).

This “blessing” was proof that Dominik mattered, while others may have thought that he mattered in a negative sense.

In the Canadian research of Wortley and Tanner (2008), social status and respect was considered a key motivation for gang membership, and mattering was recognised in statements like this about gang membership:

‘It was just more cool. I like the respect. I like the power. You walk into a place with your boys and people notice you, ladies notice you. Ya got status, you can swagger. People know you ain’t no punk.’ (Case 44: Black male, 21 years old) (p. 201).

And, an excellent example from New Zealand showed the need to matter was critical in the rise of youth gangs that emulated the LA street gangs. Jared Savage (2020, p. 199) described the emergence of the ABC racially selected street gangs:

‘Young men of mainly Polynesian heritage, disenchanted by school and family life, were drawn to one another, often simply because they lived in the same street of neighbourhood. Searching for a common bond, many felt connected with the hip-hop culture of the United States, where their heroes rapped lyrics about growing up poor, wore heavy “bling” jewellery, glamourised street feuds and violent retribution, and sexualised women as property.’

Cults are phenomena similar to gangs and they attract vulnerable, alienated people. Jeff Guinn (2018) examined the case of Jim Jones and the People’s Temple in Jonestown, and he noted that in the early days of establishing the People’s Temple, for the young members the temple offered an alternative to the gangs. And, in the final days when some families wanted to leave Jones reminded them that they mattered, and they were parts of everyone’s families (p. 430).

In English social interaction, the adults may use a formal, social exclusionary strategy referred to as being sent to Coventry, which is deliberate ostracising a person who may have been committing an indiscretion that has offended a group of people:

After upsetting Maryanne, the class sent Billy to Coventry, and no one spoke to him or acknowledged him, so his life at school became miserable.

Mattering and Students

The concept of mattering underwrites the relationships in classrooms, yet the words are rarely spoken in Australian schools because we use other words to express this acknowledgement. A quick Google search reveals up to 100 synonyms being offered, and classes and schools often make Good Citizenship Awards, Christian Acts Awards, Kindness Awards and other values-based awards.

At Dayton Primary School (a newly built primary school), we (authors Boyd and Lehr) shared the idea of mattering in our weekly newsletter to see what reactions it elicited, and then to work on developing this concept in our school community. At Dayton Primary School, our vision is to create a ‘sense of belonging’ for each student in order for them to, ultimately, be successful. Matched with this, is the imperative that students will feel safe, included, have trust and respect, and feel valued. In other words, that they know they matter and feel that they belong in our school. We recognise that all behaviour stems from the need to belong - to matter.

In our newsletter, we wrote:

'We want all our Dayton PS students to feel that they matter and we have previously outlined the importance of relationship building for this. Yet, it is important to remember that it is not ALL about building positive relationships (and even being a friend to our students), but that helping students feel that they belong and that they matter requires building positive relationships AND establishing clear boundaries/expectations. It isn’t an either/or situation It is a ‘you can’t have one without the other’ scenario. To create safe learning environments for our students, it is vital that we show that each child matters to us and that we care about them, but it is even more needful that we show that they matter enough to us that we want them to know the boundaries and expectations of how they will behave and interact at school.'

Whilst we can’t control what is taking place for our students outside of our school context, we can control what happens when they are at school. We can help our students feel that they matter and that they belong, all in a safe learning environment where positive relationships between staff and students are forged, and the expectations for behaviour at school are clearly articulated and consistently reinforced. From experience, all children want to know that they are cared for, but they also want to know where the boundaries are and what is expected of them. There is no safety in ambiguity and inconsistency. Clarity of expectations, shared by teachers who are warm and welcoming, yet firm and fair, leads to students feeling like they matter. Thus, ensuring they can learn to their full potential.

Organisational Mattering and School Staff Relationships

Education is based on multi-dimensional human relationships, and educational leaders who understand mattering know how to work the concept. Peter Browne, a former Director General of Education in Western Australia, never attended a meeting without perusing a list of attendees, as he walked through the room he recalled names and events from each person’s past. School leaders were pleased to be remembered, and being able to discuss commonly shared memories. In announcing his retirement Peter reiterated the mattering clause by saying, “I make sure that when I visit a school, I even remember the name of the school gardener’s dog.” At that time, that was an important entre into rural schools where some gardeners still brought their dogs to school. Importantly, all the school leaders felt they mattered because Peter remembered their names and shared experiences in their lives.

Organisational mattering according to Reece, Yaden, Kellerman, Robichaux, Goldstein, Schwartz, Seligman and Baumeister, R. (2019) relates to actions, not feelings:

‘Organizational mattering is distinguished from previous formulations by one central tenet: at work, mattering is a consequence of successful actions. According to this view, an employee knows they matter due to self-assessment and recognition of their actions, not because they express emotional dependence. To be sure, expressions of collegiality and social support among co-workers are generally positive indicators of a healthy work culture - but they do not specifically inform this sense of mattering’ (p. 4).

With school staff we can see the overlap between mattering and self and group efficacy, where high levels of mattering result in high levels of self and group efficacy. Albert Bandura developed the concepts of self and group efficacy, and he stated that there were four main forms of efficacious influence:

- Mastery experiences that involve developing “… cognitive, behavioral and self-regulatory tools for creating and executing appropriate courses of action….

- Vicarious experiences by watching other in a comparative sense.

- Social persuasion developing self-affirming beliefs.

- Physiological and emotional states and positive moods (Bandura 1999, p. 3).

Underwriting, each of these influencing factors is the link with the concept of mattering, and success plays an important role in the development of the individual mattering equation.

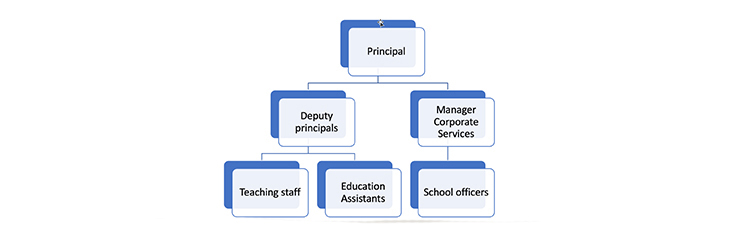

Teams are a manifestation of mattering, and growing staff teams is the major challenge for all school leaders. General McChrystal’s (2015) concept of a team of teams is, in reality, the end product of a developmental sequence starting with hierarchical organisational charts. A school, or any organisation, cannot develop a team of teams straight up, because the rules, trust and understandings, need to drive the developmental process. We are all familiar with the traditional, hierarchical school structure. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1 School Administrative Structure (Hierarchical model).

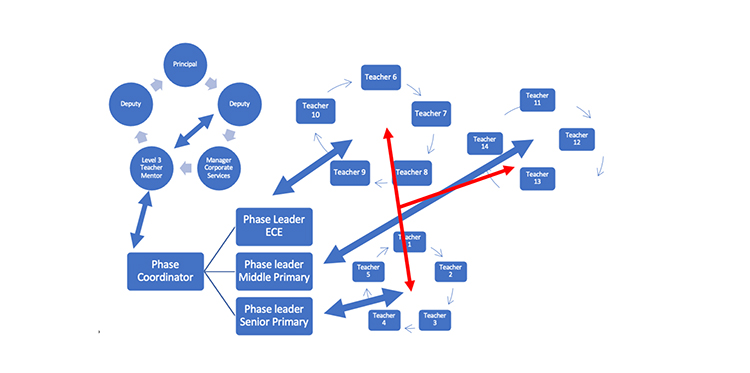

As schools start to develop a collective sense of direction based on trust and mattering, it becomes possible for the team of teams to grow either overtly, or covertly. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2 A Team of Teams (Simplified)

As with all schools, there are formal relationships and informal relationships, and when all of the staff feel they matter and have a contribution to make, co-learning takes place, and the school operates at optimal levels.

Discussion

In this paper the authors propose that mattering is a long-neglected concept that is critical to developing organisational teams. Stan McChrystal’s concept of a team of teams is the way forward, but there is important preparatory work to be done before schools get to that stage of development.

In schools we are faced daily with two aspects of the mattering issue:

- How do we progress the mattering issue?

- And, what do others do to grow or destroy the student’s mattering status?

Clearly, mattering is important in the development of every individual’s self-esteem and there are good and bad actions developing from the addressing of this issue, that teachers must address. The forming of gangs and bullying by students who want to be noticed and mattering is something that school staff deal with constantly, even though it is often dismissed as attention seeking behaviour. Such action can be overt, or quite covert, as can be seen with the action of Queen Bees and wannabees, as the Queen Bee dispenses the mattering status to her followers (Harley & MacNeill, 2017, p. 26).

‘Queen Bees and Wannabes is a system of hierarchy in which the friendship groups and the social standing of young girls are determined by the role they play in social groupings…. The Queen Bee reigns supreme over the other girls, and she weakens their friendships with others, thereby strengthening her own power and influence. She isn’t intimidated by any other girl and her friends do what she wants them to do.’

Schools can address the mattering issue at the individual, and whole-school cultural levels. The resultant cultural changes that promote students’ self-esteem and senses of mattering pay dividends across every aspect of the schools’ operations, which is the starting point of the good to great journey, recognising the importance of social-emotional learning.

Resource

To obtain a Power Point presentation on Mattering please email [email protected] and we will send it to you free of charge.

References

Akiva, T., & Robinson, K.H. (Eds.), It takes an ecosystem: Understanding the people, places and possibilities of learning and development across settings. Information Age Publishing.

Barclay, R. (2018). Alienation. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/alienation

Bandura, A. Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In Albert Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in changing societies (Chapter 1, pp. 1-45). Cambridge University Press.

Carey, R.L. (2019, September). Imagining the comprehensive mattering of black boys and young men in society and schools: Toward a new approach. Harvard Educational Review, 89(3), 370-396.

Carey, R.L., Polanco, C., & Blackman, H. (2022). Mattering in allied youth fields: Summoning the call of Black Lives Matter to radically affirm youth through programming. In T. Akiva, & K.H. Robinson (Eds.), It takes an ecosystem: Understanding the people, places and possibilities of learning and development across settings (pp. 67-86). Information Age Publishing.

Flett, G.L. (2022). An introduction, review, and conceptual analysis of mattering as an essential construct and an essential construct and an essential way of life. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/07342829211057640

Guinn, J. (2018). The road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple. Simon & Schuster.

Harley, V., & MacNeill, N. (2017, November). Queen bees, wannabees, relational aggression, and inappropriate socialisation. Australian Educational Leader, 39(4), 26-28.

McChrystal, S. (2015). Team of teams: New rules for engagement for a complex world. Portfolio/ Penguin.

Prilleltensky, I., & Prilleltensky, O. (2021). How people matter: Why it affects health, happiness, love, work, and society. Cambridge University Press.

Reece, A., Yaden, D., Kellerman, G., Robichaux, A., Goldstein, R., Schwartz, B., Seligman, M., & Baumeister, R. (2019). Mattering is an indicator of organizational health and employee success, The Journal of Positive Psychology. doi:10.1080/17439760.2019.1689416

Robinson, K.H., & Akiva, T. (2022). Introduction: A new way forward. In T. Akiva, & K.H. Robinson (Eds.), It takes an ecosystem: Understanding the people, places and possibilities of learning and development across settings (pp. 3-11). Information Age Publishing.

Rosenberg, M., & McCullough, B. C. (1979, August 27). Mattering: Inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association (Boston, MA).

Savage, J. (2020). Gang land: New Zealand’s underworld of organised crime. HarperCollins Publishers.

Stuart, F. (2020). Ballad of the bullets. Princeton University Press.

Tutu, D. (1999). No Future without forgiveness. Rider (Random House).

UKEssays. (November 2018). Youth from broken families are susceptible to join gang. Retrieved from https://www.ukessays.com/essays/criminology/youth-from-broken-families-are-susceptible-to-join-gang-criminology-essay.php?vref=1

Wortley, S., & Tanner, J. (2008). Respect, friendship, and racial injustice: Justifying gang membership in a Canadian city. In F. van Gemert, D. Peterson, & I. Lien (Eds.), Street gangs, migration and ethnicity (Chapter 12, pp. 192-208). Willan Publishing.

Citation

MacNeill, N., Boyd, R., & Lehr, R. (2023, June). Mattering: Resurrecting this understated concept in school practices. Education Today https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/Mattering-5951