Leading change and innovative practice: Building teacher capacity

There is a rumour that when joints get brittle, skin crisps and wrinkles from constant exposure to the elements, and the muscles relax, and relax, and relax, PE teachers have no other option than to seek school headships. What do you think? Regardless of what their pedigree is, what we can agree on is that the role of principals is becoming more and more complex.

Managing and leading continuous change has become one of the most significant challenges for school leaders. They have not only been tasked with initiating change in their school settings but have also needed to be responsive to the changing demands of external stakeholders including parents, governments and education authorities.

Scrutinised by a constantly hovering and forensically, yet often misdirected, media, schools and educators have had to respond to accountability measures both real and ridiculous. Nevertheless, changes have been made, often at the cost of their own wellbeing and the wellbeing of their staff. So, if change is a constant, principals are faced with the challenge of how to best lead and manage it. This article focuses on ways in which principals can undertake measures that enable their schools to be change responsive whilst minimizing the negative impacts on what is most likely an already innovation-fatigued teaching staff.

Riley’s (2015) recent principal occupational health, safety and wellbeing survey certainly confirms concerns of principals who report heavy workloads, feelings of a lack of support from education authorities, threats of bullying and violence, higher levels of stress and burnout than the community at large, and a lack of understanding by colleagues as to what their roles involves. It is not surprising then that the survey (Riley, 2015) also shows there’s a lack of ‘enthusiasm’ for deputy heads and assistant principals to ‘step up’ to the most senior leadership position. Interestingly, these concerns resonate strongly with those provided by new graduates as to why they are leaving the profession (Buchanan, et al., 2013, cites 30–50% leave in their first five years). Yet principals and graduates share many positives.

Fundamentally, they both possess what Fullan (2011) describes as a strong moral purpose. They want to make a positive impact, they’re prepared to accept the difficulties inherent in their jobs because they are intrinsically motivated by a strong sense of purpose and begin their roles with an overflowing cup of optimism and enthusiasm confident in the knowledge that their efforts will, in the end, be worthwhile.

So, what goes wrong? In talking with heads of schools, one of the most significant concerns they identify is the personal and professional isolation that often comes with the job. Teachers are renowned as a talkative bunch – often preferring to discuss student and teaching issues over morning tea and lunch rather than the footy score, or even the weather!

Heads usually don’t have that luxury – their work is often highly privatised and by its nature, isolated. Yet, it will remain this way and continue to impact negatively on their professional health and wellbeing if new ways of de-privatising and distributing their practices are not achieved. The challenge therefore, is how can principals, since they have the badge, grow professional environments where embracing change is not viewed with professional suspicion, problems are seen as opportunities and the environment for all practitioners becomes one based on collaboration and engagement rather than retreat to old practices and resistance? Addressing these core practices goes a long way in dealing with feelings of isolation, lack of collegiality and challenge the out dated view that such negatives are just part of the job and only the professionally strong will survive.

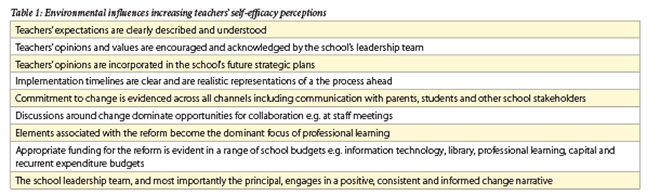

This article looks at ways in which principals can be key influencers in shaping the culture of their schools and in so doing, create workspaces that are more professionally fulfilling for graduates, teachers and for themselves. There are a number of areas that principals can have influence over in affecting positive engagement with change. Let’s first identify areas of focus. From my doctoral research, teachers identified a range of elements that increased their sense of self-efficacy and professional capacity and promoted positive engagement with the implementation of the Australian Curriculum. These are elaborated in Table 1.

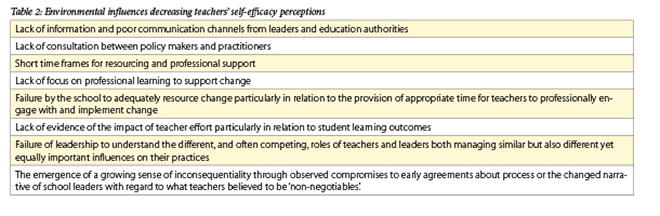

Environmental factors that were negative influences on teachers’ perceptions of self efficacy and their professional capacity to engage positively with change are identified in Table 2.

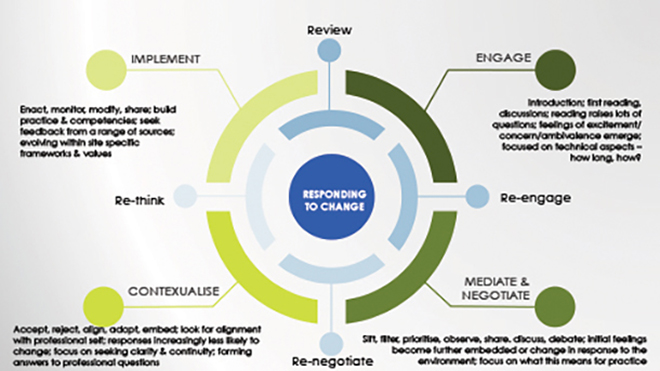

So, how can these positive attributes and qualities be achieved? What does the process of engagement to implementation look like and where might the principal be able to exert influence in guiding the direction of engagement towards positive implementation? Resistance and negative responses are not desirable, nevertheless, principals want to encourage positive yet informed engagement from teachers that may mean critiquing the process or program resulting in modifications to the change initiative. An informed way of achieving this is understanding the thinking behind the formation of responses. Figure 1 provides a relatively simplistic outline of how teachers engage with change. The important thing to note is that their actions are both cyclical (in both directions) and uni-directional, time between phases is arbitrary, and responses are multi-layered as seen in the two cycles – Engage, Mediate, Contextualise, Implement, Re-engage, Re-Negotiate, Re-Think and Review – and so it goes on. While the entry point is at initial Engagement, the stages that follow can be both sequential and concurrent depending upon the nature of the change and the implementation model and timeframe adopted.

So, how can these positive attributes and qualities be achieved? What does the process of engagement to implementation look like and where might the principal be able to exert influence in guiding the direction of engagement towards positive implementation? Resistance and negative responses are not desirable, nevertheless, principals want to encourage positive yet informed engagement from teachers that may mean critiquing the process or program resulting in modifications to the change initiative. An informed way of achieving this is understanding the thinking behind the formation of responses. Figure 1 provides a relatively simplistic outline of how teachers engage with change. The important thing to note is that their actions are both cyclical (in both directions) and uni-directional, time between phases is arbitrary, and responses are multi-layered as seen in the two cycles – Engage, Mediate, Contextualise, Implement, Re-engage, Re-Negotiate, Re-Think and Review – and so it goes on. While the entry point is at initial Engagement, the stages that follow can be both sequential and concurrent depending upon the nature of the change and the implementation model and timeframe adopted.

What is important to note here is that there are critical junctures in this cycle where the actions of the principal are essential in promoting positive engagement and implementation.

The first reading of policy or changed practice, for instance at the Engagement level provides the most important opportunity for the principal to introduce the change narrative, that is well-articulated and considered and presents alongside it, the critical links between the change initiative and a variety of school based frames – time frames, policy frames, strategic and operational frames, mission and values frames. In doing this early and consistently, the actions of the principal initiates a change process based on trust and builds professional confidence and capacity. No doubt many questions will be raised which need to be addressed in a meaningful way that instills confidence without appearing to be inflexible or arrogant. At this point, it is important to identify the means by which collaboration will be undertaken and what the full cycle of development to implementation looks like.

After initial engagement and considerable discussion, the principal has the opportunity to ensure workplace conditions and structures are in place to encourage positive responses. Ensuring that the change sits within the teaching and learning context of the school enables teachers to make links between change and what should lead to, improved outcomes for their practice. Visualising the evidence of their effort as early as possible builds confidence amongst teachers. Principals can ensure that middle tier leaders have had enough time to fully grasp the implications of the change initiative and supportive structures are in place to promote positive engagement such as meeting schedules, access to professional learning, timetabling allowances, staff working spaces, the composition of teams and the feedback and reporting timelines and frameworks have been effectively negotiated and are in place.

The evidence of these efforts is then all about the school and teachers can ‘sense’ the authority of the change initiative. The energy generated from these practices should not be underestimated and intuitive principals will be ‘reading’ the landscape to identify what more needs to be done, where the momentum is gathering and where it is not. Being somewhat of an outsider, it’s an opportunity for the principal to consult, re-focus and review and may result in redirecting energies, actions and timeframes. This should not be seen in any way as acquiescence, more an informed and flexible response to what’s happening on site and seen by teachers as a nod to their professionalism. These actions enable teachers to contextualise the change, to develop alignment between new and current practices and policies, and to embed new procedures into programs. Handled carefully and sensitively, it enables teachers to look beyond the mechanics of the change and develop another layer of professional skills to add to their professional identity. All along, developing such environments and actions is simultaneously building professional trust.

Implementation provides an opportunity to look back to move forward and examine the relationships between what was initially intended in early discussions with what is enacted. The change narrative is well established and embedded in practice and those who still may be resistant will require careful management (rather than leadership at this stage). While teachers may be focused on the immediate and the short term, principals have another layer of reporting frameworks. Therefore, also important at this stage is the gathering of rich and appropriate data to gain clarity around intended outcomes. Communication is key to meaningful reflective practice from which new levels of engagement emerge.

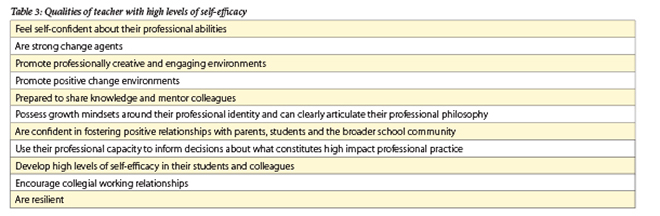

As principals work in this way, the self-efficacy of teachers increases. This is important since there are many positive attributes of highly self-efficacious teachers. A summary of these attributes is outlined in Table 3.

In summary, there are a multitude of reasons as to why more professionally engaging and stimulating working environments are needed in the education sector. For the purpose of this article, it has been about identifying the critical role the principal plays in creating and establishing the environmental conditions that support positive engagement practices in times of change. What is also important to understand is that not only do teachers benefit from conditions that support and nurture their professional practice, but principals who act to address these concerning elements in more distributive, consultative and collaborative ways are addressing their own negative feelings associated with their roles. And, given that change is a constant, the wellbeing of principals mandates that this re-envisioning of roles and professional relationships happens sooner rather than later.

References

Buchanan, JD, Prescott, AE, Schuck, SR, Aubusson, PJ, Burke, PF & Louviere, JJ (2013). Teacher retention and attrition: Views of early career teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38 (3).

Evans, D (2016). Working the space: locating teachers’ voices in large-scale mandated curriculum reform. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Southern Queensland. https://eprints.usq.edu.au/29426/

Fullan, M (2011). The Moral Imperative Realized. Corwin, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Riley, P (2015). Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey. Institute for Positive Psychology and Education. Faculty of Education and Arts. Australian Catholic University, Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia, 3605