Ecopedagogy: Teaching sustainability practices in school

The education of young children needs to be educative, positive and reassuring, so that these children develop a glass half-full, reassuring outlook on life because the alternative is that an overly critical view is less conducive to promoting children’s positive mental health. Within this context, ecopedagogy is a developing area of interest in environmental education, and it gives teachers useful insights into teaching and learning in a modern, environmentally sensitive context. While ecopedagogy addresses diverse areas of learning across the curriculum, it fits the curriculum particularly well in relation to equity and sustainability issues.

In a school-based work-in-progress program our students have access to a variety of fruiting trees including “bush tucker” plants, and they address ecological problems such as the reduction of plastic waste and composting, which build on their positive biophilic (an innate relationship with Nature) tendencies (Hand, Freeman, Seddon, Recio, Stein, & van Heezik, 2017).

In this paper the authors examined some immensely popular, place and environmentally-focussed children’s books created by the British-Australian author, Jeannie Baker, and the books were used as stimuli for students’ learning within an integrated ecopedagogic context.

Ecopedagogy and sustainability

Eco meaning not harmful to the environment, and pedagogy, meaning the way teachers teach and the methods they use to engage, influence and teach their students.

Ecopedagogy is an awareness in teachers of our ever-changing environment and the impact it has on our planet. For example, if teachers do not embed ecological knowledge, skills and beliefs into their daily practice, the next generation of adults will lack these skills and sustainable awareness, and will not be able to continue the cycle of a sustainable future.

Teachers need to use their influence as role models to embed these ideals into the minds of young Australians. Ecopedagogy has to be an observe, analyse and act attitude that is modelled by teachers for their students. The attitude needs to be along the line of this: small changes become big problems – small solutions and powerful daily efforts make for a more sustainable future. We want to close the gap on mindsets such as “This problem is bigger than me”, and “What I do won’t make a difference,” but rather encourage the “We all have to play our part,” and “Many hands make light work” attitude.

It goes back to the same old story, if the teachers don’t care, the students won’t care and if that is the case, what kind of world will we be living in, in 50 years' time? So, let’s care! Let’s encourage and inspire passionate and sustainable young minds to do our part in tackling this worldwide problem.

Underwriting the Australian national curriculum is the national commitment to sustainability as a cross-curriculum priority that is fundamental to:

- Understanding the ways social, economic, and environmental systems interact to support and maintain human life

- Appreciating and respecting the diversity of views and values that influence sustainable development

- Participating critically and acting creatively in determining more sustainable ways of living (Australian Curriculum, n.d.).

With this national drive to develop the values associated with sustainability, it remains the responsibility of the Australian states to develop this complex topic into engaging teachable lessons, and this is where ecopedagogy can guide classroom teachers.

The transference of cognitive learning and information into embedded values and beliefs is an area of learning that is almost mystical and not well understood. It is a mistake for teachers to think teaching a lesson on say respectfulness will mean that the students all become respectful. However, not making students aware of the values that society espouses is not an alternative, and Kohlberg’s easily adaptable Stages of Moral Development provide a supplementary observational scaffold on which to judge students’ behaviours.

A sense of sustainable place

The traditional approach in HASS (Humanities and Social Sciences) curriculums is to focus on the students’ home environment first, and then in expanding circles to develop the students’ knowledge from the home environment to the town, region, state, continent and then the world. In the article, "The Influence of Nature on a Child’s Development: Connecting the Outcomes of Human Attachment and Place Attachment," the authors Little and Derr (2020) noted that human and place attachments are important in developing individuals' senses of attachment:

‘Secure human attachments also foster resilience in that children are better able to respond to and cope with stress. Secure place attachments are linked to the presence of nature, social bonding, and emotional and cognitive processes. This is consistent with emergent resilience research with children which suggests that nature can play an important role in fostering resilience.’

The assertion that place is so important in the development of children's resilience seems to underwrite the intuitive curriculum model of teaching HASS/ Social Studies.

Jeannie Baker – Window

Window is a wordless picture-book that was ideal for teaching students observation and analytical skills. Dobrin and Morey (2009, p. 10) spoke of the connection between pictures and language as familial, and "… we must understand both how images of environments work and the lingual "messages" that might lie behind those images". Jeannie Baker (2002) in her Author's Note stated:

‘In this book I set out to tell the complicated issue of how we are changing the environment without knowing it. This change is hard to see from day to day but it is nevertheless happening and it is happening fast.’

She challenges the readers by drawing a connection between the window and the window of our minds needing to be opened, giving us a better understanding of how we personally impact the environment incrementally, and how we can make a difference.

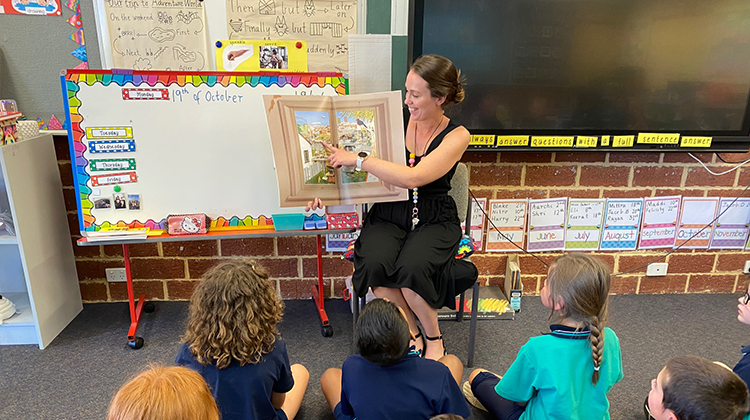

My Year 2 class read and analysed Jeannie Baker's book Window. As the students analysed the few minor, but mostly major changes in the depicted environment, the students commented on how the sustainability message in Window reminded them of the problematic themes in Dr Suess’s book The Lorax.

Picture 1 A mother with a young baby looking out at an overgrown back yard with an outside toilet. There is a variety of birds, butterflies, and a ginger cat.

The students described this as: “In the picture I can see a pond with water, a snake, an outside toilet, bushy trees, green grass birds, and a kangaroo.”

Picture 2 (two years later): Mum is hanging out the washing on a clothes-line and the two-year-old baby is at her feet, accompanied by the ginger cat. The yard is now fenced, trees have been removed and an area is ploughed. Three galahs are flying over the ploughed land.

The students said: “In this picture I can see a washing line, a fence, a gate, and less trees.”

Picture 3 (two years later): The baby (Sam) is now four years old, and he can be seen standing on a box, accompanied by the ginger cat, and dressed in a superman outfit. The backyard is now fenced and a road divides Sam's house from the new house we can see, just beyond the outside toilet.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see socks on the washing line, a lake, some birds in the trees, and a car.”

Picture 4 (two years later): The once tree filled field across the street is now grass with a new house built on it. There is a tractor next to the new house that is ploughing some dirt. A young lady is riding a horse along the road outside Sam’s back gate. A new black car has appeared and is parked on the side of the road. A little girl is waiting at Sam’s gate for him, they are both wearing the same blue jumper and each have backpacks. It is presumed that they are off to school.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see kids playing, a lady, houses, some socks, a chopping machine, and a girl.”

Picture 5 (two years later): As Sam writes his name in the mist of the glass we look out his window and see that the land next door to Sam’s house, that was trees and bush land, has now been bulldozed. The outhouse toilet is looking very old and weathered and there is a paved concrete driveway now inside Sam’s backyard with a new car parked in it. There is no longer a string fence surrounded Sam’s Mum’s property, it is now a wooden picket fence. In the distance, another two houses have been built.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see a cat, a tree, trucks, cars, homes, fences, and a ladder.”

Picture 6 (two years later): Sam now has a next-door neighbour as a house has been built right next door where that ploughed dirt was. They share the wooden picket a fence. There is a new metal washing line in Sam’s backyard as well as a tin shed. New cars and a drink truck appear on the road. The empty block of land across the road is now ‘For Sale’ and three more houses have appeared in the distance. Children are playing jump rope in the street while Sam’s ginger cat suns itself on the roof of their tin shed.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see less trees, two more houses, a food truck, and a tree getting chopped down.”

Picture 7 (two years later): Sam is now 12 years old. The outhouse toilet in the backyard is now gone. There is a man-made pond in the yard that Sam is aiming his sling shot at through the open window. New cars and a ute appear as well as more people on the street outside Sam’s back gate. Six new houses have been built in the land across the road and the trees in the distance have now vanished.

The students described this as: “I can see trucks, cars, a shed, not many trees, a man-made lake, and firewood.”

Picture 8 (two years later): Sam’s next-door neighbour’s backyard trees have now been cut down and more roads and houses have been constructed. There are only 4 single trees standing alone on the hills in the distance, the green bushy hills have diminished and are now sandy dirt hills.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see three kids, two birds, cars, an apple that is eaten, and more houses instead of trees.”

Picture 9 (two years later): This picture shows Sam greeting his ginger cat as it jumps through the window. It is night-time, the picture shows the array of lights coming from the houses in Sam’s now ‘suburb’. The closest being his immediate neighbours, so close that you can make out the curtain patterns and one of the neighbour’s outline who is also looking out of their window.

The students described this as: “In the picture I can see lights, the next-door neighbours, and their curtains.”

Picture 10 (two years later): Fast food chains are arriving in town with a Mc Donald’s sign across from Sam’s backyard. An array of road vehicles (trucks, vans, cars, motorcycles) line the streets. The house across the street that once saw elderly ladies knitting out the front, is now boarded up at the doors and windows. The once tree covered hills are now crowded with housing. One paperbark tree lay standing in Sam’s backyard.

The students described this as: “In the picture I can see chip packets, burger wrappers, bikes, and shops.”

Picture 11 (two years later): Housing in the area is increasing and is encroaching closer and closer to Sam’s house. There is the first unit block among the housing and a supermarket has opened up across the street where the boarded up house was. There is a cross walk outside Sam’s back fence and graffiti on the walls of some of the buildings. Sam is now an adult and has a partner called Tracy and what looks like a new ginger cat.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see litter behind a moving truck and only one tree.”

Picture 12 (two years later): Sam and Tracy are moving house, an there is a moving van in their driveway. The supermarket carpark across the street is completely filled with cars and another unit block has been built on what used to be to tree covered hillside. Smoke gushes out of a large building in the distance. More houses and buildings have been built since the last picture and there is a mural painting of trees on the side of a building near the Mc Donald’s.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see rubbish, a coke poster, and a keep off the grass sign.”

Picture 13 (two years later): Sam has just turned 24 and is settling into his new house. He holds a small baby in his arms. As he looks out the window, we see what Sam sees. A bush land, similar to the one we saw in the first picture. There are trees, bushes, greenery. It looks calm and peaceful just like the first picture. The students can see the city in the far distance. Sam has moved his new family away the hustle and bustle of city life. Only to find out that it might be just about to happen again, right before his child’s very own eyes, through their new window. There is a house block for sale sign in amongst the bush land across the road.

The students described this as: “In this picture I can see some trees, a bird, and a for sale sign. I think his new place is going to be crushed down and more houses come.”

Conclusions

There is a popular aphorism in teaching that values are caught, not taught. Therefore, ecopedagogy is a sophisticated pedagogic process that delivers the cognitive knowledge but enhances social-emotional-axiological learning through discovery at a personal level. It is never possible for a teacher to tick a box claiming to have taught the students ecological awareness in Year 2 or Year 10 because behavioural confirmation may not appear until the child reaches adulthood, and then that measure has been contaminated with thousands of unrecorded, influential incidents. However, from an educational viewpoint, doing nothing about sustainability and ecological issues is not an option because it is an integral part of preparing students for a place in future society.

In the students' analyses it was possible to see that all of them had grasped the main idea from the book Window. The success of this lesson can be seen in Student 9's writing where, using a lot of exclamation marks to emphasise his message, he wrote:

In the book called Window the land used to be beautiful and peaceful with an outside toilet. But one day people started to cut down all the trees! When he was two there was another house. They bought the house and a horse. They also took his pond! When he turned four they built a road and started to build a city! It is really bad! Suddenly, the hills started to get bare, the city grew and less trees grew! Then it was so big they decided to move houses to a better place and they did. The city was so big that you can see it from far away. I know what’s going to happen, it will happen again to Sam’s new house.

References

Australian Curriculum (n.d.). Sustainability. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/cross-curriculum-priorities/sustainability/

Baker, J. (2002). Window. London: Walker Books.

Dobrin, S.I., & Morey, S. (2009). Ecosee: A first glimpse (pp. 1-19). In S.L. Dobrin & S. Morey, Ecosee: Image, rhetoric, nature. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Hand, K.L., Freeman, C., Seddon, P.J., Recio, M.R., Stein, A., & van Heezik, Y. (2017, January 10). The importance of urban gardens in supporting children’s biophilia. PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America), 114(2), 274-279.

Little, S., & Derr, V. (2020). The influence of Nature on a child’s development: Connecting the outcomes of human attachment and place attachment (pp. 151-178). In: A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, K. Malone, & E. Barratt Hacking (Eds), Research Handbook on Childhoodnature: Assemblages of childhood and nature research. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Cham.