Computer failure

Above: Table 1. Trends in mathematics performance and number of computers in schools (OECD, 2015)

Australian schools have seen a huge push in recent decades to bring more computing and IT use into classrooms. Has it produced positive results? The evidence suggests that far from improving student outcomes, our focus on IT has been detrimental. This article discusses the consequences of IT on student performance, cognition and beyond the classroom. It also examines the impact IT has on teaching, the cost involved, and what benefits their might be in its use.

Academic outcomes

The OECD, reporting on years of PISA data, has found no improvement in student performance in countries where IT use was more widespread (OECD, 2015). In fact, there is a negative correlation – the more IT use, the lower scores in certain areas such as reading and mathematics are (Jacks, 2015a). Individual systems provide the evidence: in South Korea and Shanghai, where there is less in-class computer use, scores are high and rising (Coughlan, 2015).

In countries with high IT use inside classrooms, results are not only dropping down the rankings, but falling in real terms. Countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Sweden fall into this category. Australia has the highest number of IT devices per student in the world; it is also going backwards in PISA and many NAPLAN outcomes have flatlined for many years. If the OECD is to be believed, our use of IT in classes is having a harmful effect on learning.

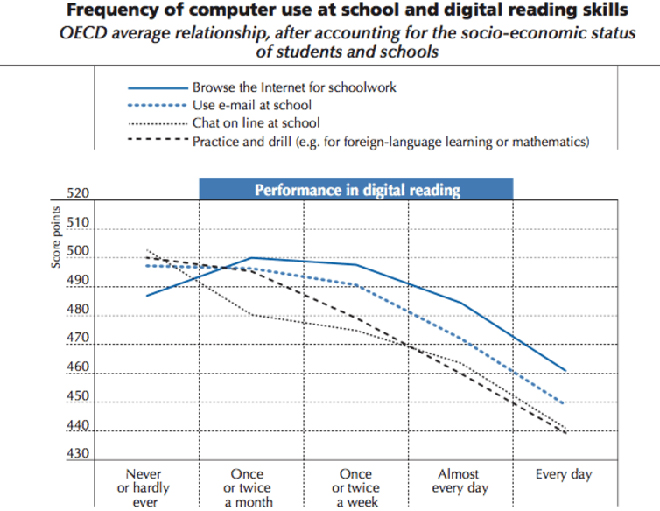

Tables 1 (top of page) and 2 show the negative effect computers have on numeracy and digital reading skills.

Table 2. Frequency of computer use at school and digital reading skills (OECD, 2015)

Cognitive effects

Research has shown that screen time for pre-school students replaces time spent on more impactful learning activities such as language and play-based interactions with people (Radesky, Schumacher, & Zuckerman, 2015). It also reduces time spent in sensorimotor activities. Given the importance of early childhood education to later education outcomes, this is concerning.

When students arrive at school, using IT can often have a lower cognitive demand than traditional activities. Take researching a middle school project, for example. Before computers, a student would have to think about what subjects related to her project. She would then head to the library and look through the cardboard file catalogue. She would find 5-10 books that are loosely concerned with her topic. She would then have to look through the indexes or contents pages of all these books to work out which ones were about her topic. She would then have to read passages from the 3-4 books that had relevant information. She would then need to take notes on this information, reorder it to suit the purposes of her project and rewrite her notes to answer the research questions she had. In the IT age, a student can simply type any natural language phrase into a search engine and get a direct answer. If we think about how many times this scenario plays out across a student’s compulsory education, the lower cognitive demands add up to a very different set of learning experiences.

Ward et al. (2017) have found that cognitive capacity is reduced when people have their smartphone nearby. This seems likely to be true for iPads and other in-class IT devices also. As their research has found, they don’t need to be getting notifications, “the mere presence [...] was enough to reduce their cognitive capacity” (Ward et al., 2017). It is common to have to tell students to put their iPads face down on the desk, and any time a teacher is less than vigilant, students reach for them. As Ward’s research shows, having a device within easy reach reduces focus and performance because part of the person’s brain is actively working to not pick up or use their device.

There is also likely to be a negative effect on other mental processes. Man Book Prize winner Howard Jacobson writes how IT use has eroded his own concentration span and he thinks IT use will render most young people effectively illiterate in the near future (Cowdrey, 2017).

Empathy also suffers. Conversations in which participants have devices nearby were rated of a much lower quality, with less empathy between individuals (Misra, Cheng, Genevie, & Yuan, 2016).

In a study of students taking notes either by hand or via laptop, Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014) found that IT use also hinders comprehension. Students using laptops often took verbatim quotes, whereas note takers, because they couldn’t write as fast as they could type, had to summarise on the fly, and thus processed and understood material much better. Mueller and Oppenheimer also found that people remember more of what they write by hand than what they type using a device. This has implications for school systems that allow students to use devices in class for note taking, research and assignments.

Outside school

We also see a lot of negative effects of IT use outside the school environment. It is common to hear from families and teachers of Year 7 students, upon entering a high school that has a one to one iPad program, that the young people have been turned into screen addicts. What was supposed to be a device used to enhance learning has become a 24-hour obsession. There are numerous studies showing that longer time spent on social media via IT devices leads to anxiety and depression (see, for example: Chiou, Lee, & Liao, 2015; Lee-Won, Herzog, & Gawn Park, 2015; Marche, 2012). We now have children as young as eight with anorexia from looking at the latest ‘thinspiration’ on Instagram (Boseley, 2015). The mental wellbeing of young people has decreased significantly since 2007, the year the iPhone launched (Cowdrey, 2017).

The digital divide, between those with a lot of IT access and those without, is also exacerbated by computers in the classroom (Coughlan, 2015). The OECD (2015) also notes a number of harmful effects of internet use by young people outside school, especially their ‘inappropriate media diet’. The ubiquity of online pornography is also more of a problem for environments where young people have high levels of IT access.

Perhaps more concerning is the unknown world we are bringing our young people into. There is very little research done into the effects of screen time on young children (Misra et al., 2016). Considering how widely IT devices are being adopted, and the potential for harm, this is both surprising and concerning.

Effects on teaching

It has been noted that effective teachers can produce great student outcomes with the use of technology. However, it is also true that effective teachers can produce these same results without technology use, while ineffective teachers do not improve student outcomes more if they use IT. Thus, while previously we may have thought IT was a panacea and a substitute for good teaching, it is now clear that there is no such thing. School systems also often make the mistake of putting the cart before the horse – technology is put in place in schools and only afterwards do we question the impact that it will have on learners, or how we can empower teachers to best use it (Trucano, 2005).

So how can IT use improve teaching? Firstly, training needs to be ongoing, rather than one-off. Many in-service teachers are not IT-literate enough to enhance their teaching with its use (Trucano, 2005). Secondly, training needs to be about how to use IT to improve teaching, not just on technical computing skills. How a teacher can successfully use IT depends to a large extent on their teaching style. Should IT use support traditional learning or be something completely different? The training requirements will be very different for these two options.

Financial expense

The debate about the amount of funding given to our schools has been heated. Critics of increased funding point out that large increases have not improved student results. They question what the money is being spent on. Technology in schools is a prime candidate for misspent funding. Australia has the highest level of in school computer use in the world, with one computer per student in Australia as a whole, and one hour per school day spent online, twice the OECD average. Australia has overinvested in IT (Donovan, 2015). John Vallance, headmaster of Sydney Grammar, believes the billions spent on computers is a “scandalous waste of money”. He believes funding is best spent on teachers, not technology (Bita, 2016).

We have already seen large amounts of public money wasted on interactive whiteboards and $240 million on Victoria’s ill-fated Ultranet (Cook, Preiss, & Jacks, 2017). We are now the country the most heavily invested in school IT in the world. Do we have results to justify the costs?

Benefits?

There are some benefits to school computer use, although they are limited. Using computers develops IT literacy, although it doesn’t develop language literacy (Radi, 2002). The OECD (2015) report does find that a little IT use is better than none, but more than the OECD average (i.e. Australia) is linked with lower performance.

We would also have expected an increase in IT use in schools to increase interest in IT as a subject. We often hear that computers in school and coding courses will make Australia an IT powerhouse. Unfortunately, the opposite is true. Although a recent study has stated we will need an extra 100,000 IT graduates by 2020, the number of graduates with IT qualifications has dropped significantly since the early 2000s (Jacks, 2015b). There are also far fewer students doing computing in VCE than there was ten years ago.

Conclusion

There is a lot of public information about the negative effects of computers on education outcomes. Yet school systems have devoted huge financial and human resources to making Australia the country with the most computers in school of any country in the world.

Why? This question really needs to be asked in every school in the country.

About the Author

Ben Lawless is Head of Faculty - Humanities, Aitken College, Greenvale, Victoria

www.aitkencollege.edu.au

References

Bita, N. (2016, 26 March). Computers in class ‘a scandalous waste’: Sydney Grammar head. The Australian. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/education/computers-in-class-a-scandalous-waste-sydney-grammar-head/news-story/b6de07e63157c98db9974cedd6daa503

Boseley, S. (2015). Basis for eating disorders found in children as young as eight. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/jul/23/basis-for-eating-disorders-found-in-children-as-young-as-eight

Chiou, W.-B., Lee, C.-C., & Liao, D.-C. (2015). Facebook effects on social distress: Priming with online social networking thoughts can alter the perceived distress due to social exclusion. Computers in Human Behaviour, 49, 230-236.

Cook, H., Preiss, B., & Jacks, T. (2017, 27 January). IBAC finds disastrous Ultranet project for schools was a 'corrupt' shambles. The Age. Retrieved from http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/ibac-finds-disastrous-ultranet-project-for-schools-was-a-corrupt-shambles-20170126-gtzr67.html

Coughlan, S. (2015). Computers 'do not improve' pupil results, says OECD. BBC News Retrieved 27 August, 2017, from http://www.bbc.com/news/business-34174796

Cowdrey, K. (2017). Twitter will render children illiteratre in 20 years says Jacobson. The Bookseller Retrieved 1 August, 2017, from https://www.thebookseller.com/news/jacobson-warns-screen-tech-render-children-illiterate-20-years-614881

Donovan, S. (2015). School computer use may be affecting literacy and numeracy skills, OECD study says. ABC News Retrieved 10 August, 2017, from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-09-16/computer-use-may-be-leading-to-literacy-numeracy-decline/6779986

Jacks, T. (2015a). Are iPads in schools a waste of money? OECD report says yes. The Age. Retrieved from http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/are-ipads-in-schools-a-waste-of-money-oecd-report-says-yes-20150914-gjmnqf.html

Jacks, T. (2015b). Millenials reject IT and computing subjects in VCE. The Age. Retrieved from http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/millennials-reject-it-and-computing-subjects-in-vce-20150721-gih1rx.html

Lee-Won, R., Herzog, L., & Gawn Park, S. (2015). Hooked on Facebook: The role of social anxiety and need for social assurance in problematic use of Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18, 567-574.

Marche, S. (2012). Is Facebook making us lonely? The Atlantic.

Misra, S., Cheng, L., Genevie, J., & Yuan, M. (2016). The iPhone Effect: The Quality of In-Person Social Interactions in the Presence of Mobile Devices. Environment and Behavior, 48(2), 275-298.

Mueller, P., & Oppenheimer, D. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard. Psychological Science, 25(6), 1159-1168.

OECD. (2015). Students, computers and learning.

Radesky, J., Schumacher, J., & Zuckerman, B. (2015). Mobile and Interactive Media Use by Young Children: The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown. Pediatrics, 135(1), 1-3.

Radi, O. (2002, 29 July - 3 August). The impact of computer use on literacy in reading comprehension and vocabulary skills Paper presented at the Seventh world conference on computers in education conference on Computers in education: , Copenhagen.

Trucano, M. (2005). Knowledge Maps: ICTs in Education. Washington, DC: infoDev / World Bank.

Ward, A., Duke, K., Gneezy, A., & Bos, M. (2017). Brain Drain: The Mere Presence of One’s Own Smartphone Reduces Available Cognitive Capacity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 140-154.