Circling the Drain: How Social Segregation Further Disadvantages Those in Need

As educators, we place a lot of emphasis on ensuring that the practices we put into place at the school level are effective in improving outcomes for students. But do the policies and decisions beyond the scope of the school hinder or help our capacity to ensure a high-quality education for all students? Social segregation and its impact on educational outcomes for students from a socioeconomically disadvantaged background can be a common reality within Australia, with our country identified as one of the worst for an achievement gap between socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged students. This crisis and its impact on greater society are explored through the lens of a case study from my own workplace – Clarkson Community High School.

We as a country – and in particular, as those directly associated with the education system in this country – have a moral responsibility to ensure that all children, regardless of background, receive a high-quality education. A timely reminder of this fact took the form of the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre’s report this year titled, “Educate Australia Fair? Education Inequality in Australia”. The beginning paragraphs of the report’s executive summary tell a tale that I am all too familiar with:

“The role of education as a pathway out of disadvantage has featured strongly in policy rhetoric over time. Successive governments have introduced policies that have enabled greater access to higher education. Yet there remains concern that the educational opportunities for our children are unevenly distributed across locality, with something of a ‘postcode lottery’ within major population centres in terms of educational outcomes and achievements."

The analysis in the report makes it clear that many of today’s young children will not receive a ‘fair go’ in accessing education opportunities, for no other reasons than family background, demographic characteristics and geography.” (Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, 2017).

I am an alumnus of the Teach For Australia ‘Leadership Development Program’ – this program places high-quality university graduates into socioeconomically disadvantaged schools in the hope that they will play a part in eliminating educational disadvantage. Teach For Australia (TFA) as an organisation and a movement claim the following:

Our vision is of an Australia where all children, regardless of background, attain an excellent education. (Teach For Australia 2017)

The reasoning behind TFA’s model is based on research which indicates that the leading driver for improving student outcomes is to improve the quality of teaching (Hattie 2003). Studies have also shown that students from low-socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds have the most to gain from high-quality teaching (Leigh 2010).

Although we can attempt to address socioeconomic disadvantage through the improvement of teacher quality, the roots of our system that is biased against socioeconomically disadvantaged people run deeper than are immediately clear. This article will discuss social segregation and its consideration in the aim to eliminate socioeconomic disadvantage alongside strategies such as improving teacher quality. The negative social implications resulting from social segregation are clear, which makes this issue of social segregation in education not just linked to morality, but also appealing to address from a practical perspective.

In its simplest form, social segregation is defined as the forced exclusion or separation of social classes either directly or indirectly. This is an issue because it damages the capacity for equity to be achieved in our country – those with advantage maintain or increase their advantage, whereas those with less opportunity have a steep hill to climb in order to break the cycle of disadvantage. PISA 2015’s report showed that the difference in average science scores between advantaged and disadvantaged schools in Australia was 100 points – equating over three years of learning (OECD 2015). Although there are factors linked with SES that impact educational outcomes (such as family background), there is still a clear school compositional effect. As an example, many studies confirm that a student attending a low-SES school is likely to have lower results that a similar student who attends a high-SES school (OECD 2016; Perry & McConney 2010). Trevor Cobbold sums it up effectively in his 2017 report on the Save Our Schools website:

“There is a ‘double jeopardy’ effect for students from low SES families in that they tend to be disadvantaged because of their circumstances at home, but when they are also segregated into low SES schools they are likely to fare even worse. So, increasing social segregation between schools tends to lead to worse results for low SES students and widen the achievement gap between high SES and low SES students.” (Cobbold 2017)

Alongside this negative impact on academic outcomes, a 2015 OECD report demonstrated that high concentrations of low-SES students in disadvantaged schools resulted in those students having poorer expectations for the future and more limited self-belief. On the flip side of the coin, disadvantaged students who attend advantaged schools are found to have better hopes for the future as well as perform better academically (OECD 2015). Dr. Ruby Payne in her book, “A Framework for Understanding Poverty”, states that students from generational poverty lack understanding about what are considered middle class “hidden rules” – these must be explicitly taught and modelled in order for them to be able to integrate into middle class society and break the cycle of generational poverty (Payne 2005). By limiting access to middle class peers through policies and governmental decisions that cause social segregation, we are denying students from generation poverty increased opportunities to have middle class skills and rules modelled and taught to them on a peer to peer level.

Beyond the school itself and the individual students within it, social segregation has powerful implications for wider society. Social, racial and religious segregation has been shown to breed social intolerance in communities and workplaces, which damages cohesion and understanding (and hence, overall productivity). Social segregation damages social empathy and negatively impacts the capacity for social groups to coexist in any space. There is a great amount of research which links the attendance of schools with diverse peers and an increased understanding of differences and reduced prejudice (Stuart Wells, Fox & Cordova-Cobo 2016). Hence, social segregation within schools can have dire consequences for social cohesion and potential productivity.

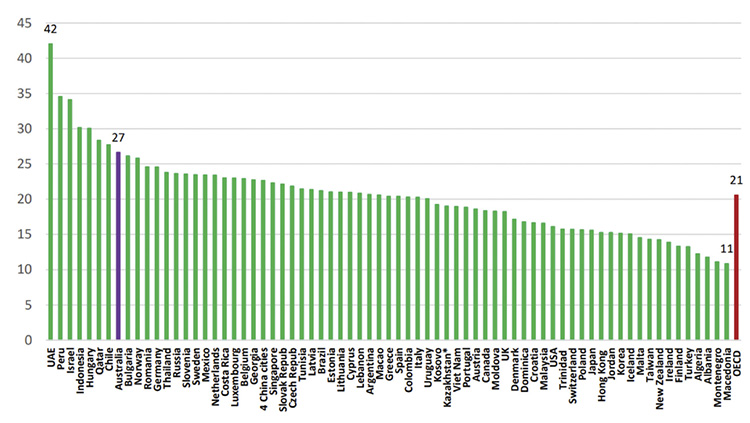

Taking all of these consequences of social segregation into account, it is important that we are aware of how Australia is progressing in terms of our level of social segregation – especially in schools. The OECD released a report in 2015 which alarmingly indicated that Australia has the 8th highest rate of social segregation out of 71 countries which take part in the OECD’s Programme of International Students Assessments (OECD 2015). Within the OECD itself, Australia demonstrates the 4th highest rate of social segregation. This is in part due to the segregation which is present between private and public schools, in which Australia ranks at 7th highest in the world. However, this dichotomy is only responsible for 16% of total segregation in schools within Australia (OECD 2015). The extent to which public and private school systems are independently responsible for social segregation is yet to be assessed.

Chart 1: Index of Social Segregation in School Systems, All Countries Participating in PISA 2015 (OECD 2015, Table III)

Current policies and bureaucratic decisions are, at times, centred on what John Hattie refers to as “The Politics of Distraction” (Hattie 2015) – decisions based on popular interest or ‘what looks good’. John Hattie details five major “distractions” in his report which categorise many of the policy decisions that are made using this school of thought. Social segregation is evident in context of the school in which I work – Clarkson Community High School (CCHS).

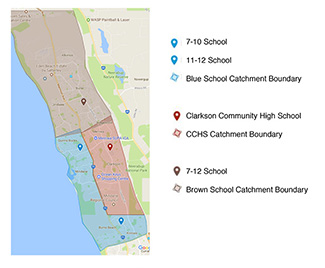

CCHS is a non-Independent Public School situated in the northwestern metropolitan region of Perth, Western Australia. The school is bounded by three other schools – one 7-12 school, one 7-10 and the 11-12 Senior College that the second school feeds into. With Clarkson marked in red, the map below demonstrates the approximate boundaries for the school catchment areas.

Figure 1: Clarkson Community High School and surrounding school catchment areas

The map above demonstrates that neighbouring schools have access to coastal suburbs with higher median house prices. This fact, coupled with median household income data from the 2016 census illustrates the socio-economic reality.

Figure 2: Suburbs and associated school catchment by median household income. De-identified suburbs colour coded by the school that exists in their catchment.

(Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2016d, 2016e, 2016f, 2016g, 2016h)

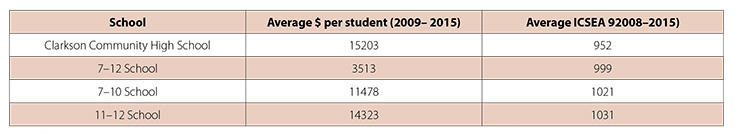

Each neighbouring school is newer than CCHS and has a higher Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA). Residualisation means CCHS is negatively impacted in terms of academic and behavioural outcomes. The level of socioeconomic disadvantage is acknowledged in the school’s ICSEA score, but the increases in per student funding are not significant enough to mitigate school compositional effects.

Table 1: Average school funding per student vs. ICSEA as per My School (Australian Curriculum 2016a)

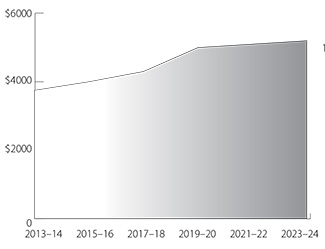

Although we sometimes consider increased funding as a solution to addressing disadvantage, it is shown that increased funding does not automatically equate to improved academic outcomes for students. To make a real change we must target areas that have the greatest impact on academic outcomes. Australian Government funding of schools has risen over time and is projected to continue to rise in the future, as per the Report of the National Commission of Audit conducted in 2014 (National Commission of Audit 2014).

Figure 3: Commonwealth per-student funding in 2013-14 dollar equivalency (National Commission of Audit 2014)

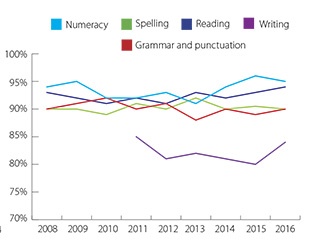

Despite increases in funding, we do not appear to demonstrate any gain in our scores on high-stakes testing - Australia is ‘flat-lining’ in academic outcomes. Although there is debate around how dire these results are - consistent achievement is not necessarily a bad thing according to some - we cannot afford to have consistent results for our most disadvantaged when we know that the results they are achieving are not demonstrative of equity in our system.

Figure 4: Australia-wide percentages of students meeting the National Minimum Requirement for assessed areas in NAPLAN over time (Australian Curriculum 2016b)

In the year that I was born, education researcher Michael Fullan stated in one of his publications,

“To have any chance of making teaching a noble and effective profession…teachers must combine the mantle of moral purpose with the skills of change agentry” (Fullan 1993).

In my lifetime, we have not yet achieved a system which does not further disadvantage those that are already disadvantaged. It is my hope that with the information presented above, the issues surrounding decision-making at a level higher than the individual school can be made clear. In the future, it is my hope that school catchment boundaries and other decisions surround school choice, merit select and specialty schools will be seriously considered through the lens of how they may disadvantage lower social classes. If we avoid making decisions based on The Politics of Distraction, and we make decisions based on outcomes with our clear moral purpose at the forefront of our decisions, we will begin the journey to ensuring that all students are given the skills they need to overcome the cycle of educational disadvantage.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016a, 'Burns Beach (WA)', database.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016b, 'Butler (WA)', database.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016c, 'Clarkson (WA)', database.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016d, 'Jindalee (WA)', database.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016e, 'Merriwa (WA)', database.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016f, 'Mindarie (WA)', database.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016g, 'Quinns Rocks (WA)', database.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016h, 'Ridgewood (WA)', database.

Australian Curriculum, AaRAA 2016a, Clarkson Community High School, Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA),, <https://www.myschool.edu.au/SchoolProfile/Index/111459/ClarksonCommunityHighSchool/48247/2016>.

AaRAA Australian Curriculum 2016b, NAPLAN Results: Time series, by Australian Curriculum, AaRAA.

Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre (2017). Educate Australia Fair? Education Inequality in Australia. Focus on the States Series, No. 5. [online] Perth, Western Australia, p.vii. Available at: http://bcec.edu.au/assets/099068_BCEC-Educate-Australia-Fair-Education-Inequality-in-Australia_WEB.pdf [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

Cobbold, T 2017, Social Segregation in Australian Schools is Amongst the Highest in the World.

Fullan, MG 1993, 'Why teachers must become change agents', Educational Leadership, vol. 50, pp. 12-.

Hattie, J 2003, 'Teachers make a difference: What is the research evidence?', in Building Teacher Quality Conference, Melbourne.

Hattie, J 2015, What doesn't work in education: The Politics of Distraction, Pearson.

Leigh, A 2010, 'Estimating teacher effectiveness from two-year changes in students' test scores', Economics of Education Review, vol. 29.

National Commission of Audit 2014, Schools funding, by National Commission of Audit, vol. 1, Australian Government.

OECD 2015, PISA 2015 Results (Volume III), OECD Publishing.

OECD 2016, Low-Performing Students, OECD Publishing.

Payne, RK 2005, 'A framework for understanding poverty'.

Perry, L & McConney, A 2010, 'School Socio-Economic Composition and Student Outcomes in Australia: Implications for Educational Policy', Australian Journal of Education, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 72-85.

Stuart Wells, A, Fox, L & Cordova-Cobo, D 2016, How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students.

Teach For Australia 2017, About Us, <http://teachforaustralia.org/about-us/>.

Photo by Johannes Plenio from Pexels