An Introduction to Invitational Theory

A number of scholars and researchers have worked together over several decades to develop an understanding of certain abstract principles and everyday facts that appear to relate to one another and which seem to influence human success or failure. This understanding has evolved into a model of practice called Invitational Theory. The term "invitational" was chosen for its special meaning. The English invite is probably a derivative of the Latin word invitare, which means to offer something beneficial for consideration. Translated literally, invitare means to summon cordially, not to shun. Implicit in this definition is that inviting is an ethical process involving continuous interactions among and between human beings.

Invitational Theory (Purkey, 1978; Purkey & Novak, 1984, 1988, 1996; Purkey & Schmidt, 1987, 1990; Purkey & Siegel, 2013; Novak, Armstrong, & Browne, 2014) seeks to explain phenomena and provide a means of intentionally summoning people to realize their relatively boundless potential in all areas of worthwhile human endeavor. Its purpose is to address the entire global nature of human existence and opportunity, and to make life a more exciting, satisfying and enriching experience.

There are five basic assumptions that are essential in understanding Invitational Theory:

- People are able, valuable, and responsible and should be treated accordingly

- Educating should be a collaborative, cooperative activity

- The process is the product in the making

- People possess untapped potential in all areas of worthwhile human endeavour

- This potential can best be realized by places, policies, programs, and processes specifically designed to invite development and by people who are intentionally inviting with themselves and others, personally and professionally.

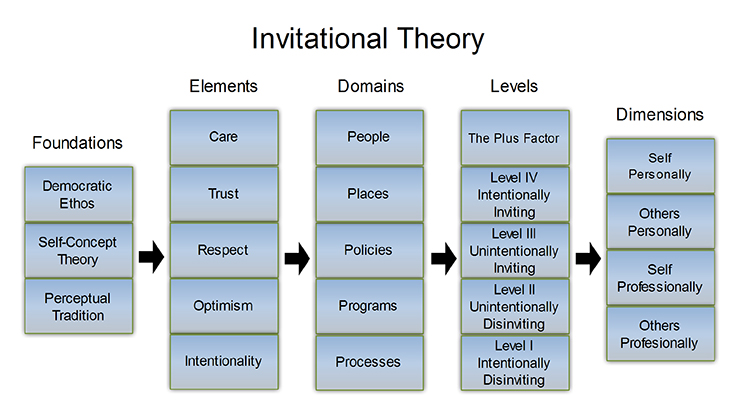

The following diagram illustrates the sections of Invitational Theory. The diagram pictures the (1) foundations, (2) elements, (3) domains, (4) levels, and (5) dimensions of the theory. Each section will be explained in turn.

Three Foundations of Invitational Theory

Invitational Theory is based on three interlocking foundations: the democratic ethos, the perceptual tradition and self- concept theory. These foundations each supported by decades of scholarly research and writing, provide Invitational Iheory with substance and structure.

The Democratic Ethos

Democracy is a social ideal based on the conviction that all people matter and can grow through participation in self- governance. Invitational theory and practice reflects this democratic ethos through deliberative dialogue, mutual respect, and the importance of shared activities. It is a “doing with,” rather than a “doing to” approach to working with people at all levels. Implied here is a respect for people and their abilities to articulate their concerns as they act responsibly on issues that impact their lives. Deeply embedded in this respect for persons is a commitment to the ideal that people who are affected by decisions should have a say in formulating those decisions.

The Perceptual Tradition

The perceptual tradition places consciousness at the center of personal reality. It proposes that people are not influenced by events so much as their perceptions of events. Human behavior is the product of the unique ways individuals perceive the world. To better understand why people do the things they do it is necessary to explore perceptions within and among individuals.

Self-Concept Theory

An important question in applying Invitational Theory is "Who am I and how do I fit in the world?" This question derives from the third foundation of Invitational Theory: self-concept theory. Self-concept is a complex and dynamic system of learned beliefs that each person holds to be true about his or her personal existence. The theory maintains that behavior is mediated by the ways an individual views oneself, and that these views serve as both antecedent and consequence of human activity. Self-concept theory was developed by Jourard (1974), Rogers (1969), Purkey (1970), Purkey (2020) and many others.

Invitational Theory offers a logical extension to the democratic ethos, perceptual tradition, and self-concept theory and builds on these three interlocking foundations. These foundations provide a structure for the five elements of Invitational Theory.

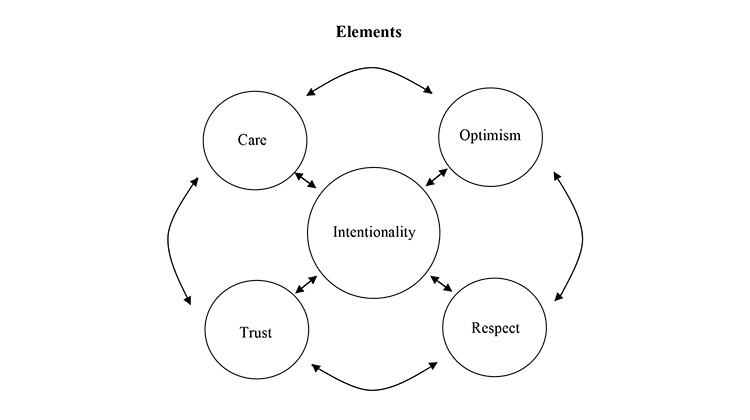

Elements

Invitational Theory is unlike any other system reported in the professional literature in that it provides an overarching and encompassing framework for a variety of approaches and models that fit with its five basic elements. These assumptions give it purpose and direction, and take the form of a stance consisting of five elements: care, trust, respect, optimism, and intentionality.

Care

Care is at the core of the inviting stance. Of all the elements of invitational theory, none is more important that a person’s genuine ability and desire to care about others and oneself. Caring, with its own ingredients, such as warmth, empathy, and positive regard, provides a person with the means to be a beneficial presence in one’s own life and the lives of others.

Trust

Human existence is a cooperative activity where process is as important as product. A basic ingredient of Invitational Theory is a recognition of the interdependence of human beings. To develop and sustain inviting relationships requires the time and effort to establish trustworthy patterns of interaction. Trust is based primarily on the memory of invitations sent, received, and acted upon successfully. Given an optimally inviting environment, that provides the resources to allow a person to make meaningful and growth-producing choices, each person will pursue his or her own best ways of being and becoming.

Respect

People are able, valuable, and responsible and should be treated accordingly. An indispensable element in any human encounter is shared responsibility based on mutual respect. This respect is manifested in the caring and appropriate behaviors exhibited by people as well as the places, policies, programs, and processes they create and maintain. It is also manifested by establishing positions of equality and shared power.

Optimism

People possess untapped potential in all areas of human endeavor. The uniqueness of human beings is that no clear limits to potential have been discovered. Invitational theory could not be seriously considered if optimism regarding human potential did not exist. It is not enough to be inviting; it is critical to be optimistic about the process. No one can choose a beneficial direction in life without hope that change for the better is possible.

Intentionality

Human potential can best be realized by places, policies, processes, and programs specifically designed to invite development and by people who are personally and professionally inviting with themselves and others. An invitation is defined as an intentional act designed to offer something beneficial for consideration. Intentionality enables people to create, maintain, and enhance total environments that consistently and dependably invite the realization of human potential.

Intentionality is so important in invitational theory that it receives special attention later in this paper.

The five essential elements of Invitational Theory: care, trust, respect, optimism, and intentionality, offer a consistent "stance" through which human beings can create and maintain an optimally inviting environment. While there are other factors that contribute to Invitational Theory, these propositions are key ingredients in moving from theory to practice.

Domains

Domains

Invitational Theory focuses on five domains that exist in practically every environment and that contribute to the success or failure of each individual. In the same way as everyone and everything in hospitals should invite health, so everyone and everything in every setting should democratically and ethically invite the realization of human potential. This involves the people, places, policies, programs and processes. These five "Ps" make up the ecosystem in which individuals continuously interact.

A starfish analogy is used to illustrate how the five powerful “P’s”, applied with steady and persistent pressure, will overcome the biggest challenges in an organization. Just as the starfish gently and continuously uses each of its arms in turn, to keep steady pressure on the one oyster muscle until it eventually opens, so will organizations meet their challenges successfully by paying close attention to the five powerful “Ps.”

Levels

In addition to its focus on the five domains of people, places, policies, programs, and processes, Invitational Theory identifies levels of functioning. Being human and less than perfect, everyone functions at each level from time to time, but it is the level at which people typically function that determines their approach to life and their ultimate success in personal and professional living.

It is useful here to contemplate the complexity of Invitational Theory. Many people think they already understand the concept of "inviting." They see it as simply doing nice things--sharing a smile, giving a hug, saying something nice, or buying a gift. While these may be worthwhile activities when used caringly and appropriately, they are only surface manifestations of invitational assumptions one makes and the inviting environments they create. These assumptions determine the level of personal and professional functioning.

The following levels provide a check system to monitor each of the Five Ps (places, policies, programs, processes, and people) found in and around any human endeavor and that reflect Invitational Theory in action.

Intentionally Disinviting

The most negative and toxic bottom level of human functioning involves those actions, policies, programs, places, and processes that are deliberately designed to demean, dissuade, discourage, defeat and destroy. Intentionally disinviting functioning might involve a person who is purposely insulting, a policy that is intentionally discriminatory, a program that purposely reduces people to functionaries, or an environment intentionally left unpleasant, unattractive, and unhealthy.

Unintentionally Disinviting

People, places, policies, programs and processes that are intentionally disinviting are few when compared to those that are unintentionally disinviting. The great majority of disinviting forces that exist are usually the result of a lack of guiding theory. Because there is no philosophy of care, trust, respect, optimism, and intentionality, policies are established, programs designed, places arranged, processes evolve, and people behave in ways that are clearly disinviting although such was not the intent.

Individuals who function at the unintentionally disinviting level are often viewed as uncaring, chauvinistic, condescending, patronizing, sexist, racist, dictatorial, or just plain thoughtless. They do not intend to be hurtful or harmful, but because they lack consistency in direction and purpose, they act in disinviting ways. People who function at the unintentionally disinviting level may not intend to be disinviting, but the damage is done. Like being run over by a truck: intended or not, the victim is still dead.

Unintentionally Inviting

People who usually function at the unintentionally inviting level have stumbled serendipitously into ways of functioning that are often effective. However, they have difficulty when asked to explain why they are successful. They may describe in loving detail what they do, but not why.

An example of this is the "natural born" teachers. Such people may be successful in teaching because they exhibit many of the caring, trusting, respecting, and optimistic qualities associated with Invitational Theory. However, because they lack the fourth critical element, intentionality, they lack consistency and dependability in the actions they exhibit, the policies and programs they establish, and the places and processes they create and maintain.

People who are unintentionally inviting are somewhat akin to the early barn- storming airplane pilots. These pioneer pilots did not know exactly why their planes flew, or what caused weather patterns, or much about navigational systems. As long as they stayed close to the ground, followed a railway track, and the weather was clear, they were able to function. But, when the weather turned bad or night fell, they became disoriented and lost. In difficult situations, people who function at the unintentionally inviting level lack dependability in behavior and consistency in direction.

The basic weakness in functioning at the unintentionally inviting level is the inability to identify the reasons for success or failure. Most people know whether something is working or not, but when it stops working, they are puzzled about how to start it up again. Unfortunately, when things stop working, people will often digress to lower levels of functioning. Those who function at the unintentionally inviting level lack a consistent stance – a dependable theory of practice from which to operate.

Intentionally Inviting

When individuals function at the intentionally inviting level, they seek to consistently exhibit the assumptions of Invitational Theory. A beautiful example of intentionality in action is presented by Mizer (1964) who described how schools can function to turn a child "into a zero." Mizer illustrated the tragedy of one such child, then concluded her article with these words:

'I look up and down the rows carefully each September at the unfamiliar faces. I look for veiled eyes or bodies scrounged into an alien world. "Look, Kids," I say silently, "I may not do anything else for you this year, but not one of you is going to come out of here a nobody. I'll work or fight to the bitter end doing battle with society and the school board, but I won't have one of you coming out of here thinking of himself [sic] as a zero.' (Mizer, 1964, p. 10).

Intentionality can be a tremendous asset for educators and others in the helping professions, for it is a constant reminder of what is truly important in human service.

In Invitational Theory, everybody and everything adds to, or subtracts from, human existence. Ideally, the factors of people, places, policies, programs, and processes should be so intentionally inviting as to create a world where each individual is cordially summoned to develop physically, intellectually, and emotionally. Those who accept the assumptions of Invitational Theory not only strive to be intentionally inviting, but once there, continue to grow and develop, to reach for the “Plus Factor.”

The Plus Factor

When people watch the accomplished musician, the headline comedian, the world-class athlete, the master teacher, what he or she does seems simple. It is only when people try to do it themselves that they realize that true art requires painstaking care, discipline, and deliberate planning over extended periods of time.

At its best, Invitational Theory becomes "invisible" because it becomes a means of addressing humanity. To borrow the words of Chuang-tse, an ancient Chinese philosopher, "it flows like water, reflects like a mirror, and responds like an echo." At its best, Invitational Theory requires implicit, rather than explicit, expression. When the educator reaches this special plateau, what they do appears effortless. Football teams call it "momentum," comedians call it "feeling the center," world class athletes call it "finding the zone, and fighter pilots call it "rhythm." In Invitational Theory it is called the Plus Factor. A good example of this factor in action was provided by Ginger Rogers, the famous actress and dancer. When describing dancing with Fred Astair, she said, "It's a lot of hard work, that I do know." Someone responded: "But it doesn't look it, Ginger." Ginger replied "That's why it's magic." Invitational Theory, at its best, works like magic. Those who function at the highest levels of inviting become so fluent over time that the carefully honed skills and techniques they employ, are invisible to the untrained eye. They function with such talented assurance that the tremendous effort involved does not call attention to itself.

Dimensions

The goal of Invitational Theory is to encourage individuals to enrich their lives in each of four basic dimensions: (1) being personally inviting with oneself; (2) being personally inviting with others; (3) being professionally inviting with oneself; and (4) being professionally inviting with others. Like pistons in a finely tuned machine or sections of musicians in a concert orchestra, the four dimensions work together to give power to the whole movement. While there are times when one of the four dimensions may demand special attention, the overall goal is to seek balance and harmony between personal and professional functioning.

Being Personally Inviting With Oneself

To be a beneficial presence in the lives of others it is essential that individuals first be inviting to themselves. This means that they view themselves as able, valuable and responsible and are open to experience. Those who adopt Invitational Theory seek to reinvent and inspirit themselves personally.

Being personally inviting with oneself takes an endless variety of forms. It means caring for one's mental health and making appropriate choices in life. By taking up a new hobby, relaxing with a good book, exercising regularly, learning to laugh more, visiting friends, getting sufficient sleep, growing a garden, or managing time wisely, people can rejuvenate their own well-being.

Being Personally Inviting With Others

Being inviting requires that the feelings, wishes, and aspirations of others be taken into account. Without this, Invitational Theory could not exist. In practical terms, good support groups are important. The “social committee” might be the most vital committee in any organization.

Specific ways to be personally inviting with others are simple but often overlooked. Getting to know colleagues on a social basis, sending friendly notes, forming a car-pool, remembering birthdays, enjoying a faculty party, practicing politeness, celebrating successes, and respecting differences are all examples of Invitational Theory in action.

Being Professionally Inviting With Oneself

Being professionally inviting with oneself can take a variety of forms, but it begins with ethical awareness and a clear and efficient perception of situations and oneself. In practical terms, being professionally inviting with oneself means trying a new method, seeking certification, learning new skills, returning to graduate school, enrolling in a workshop, attending conferences, reading journals, writing for publication, and making presentations at conferences.

Keeping alive professionally is particularly important because of the rapidly expanding knowledge base. Perhaps never before have knowledge, techniques, and methods been so bountiful. Canoes must be paddled harder than ever just to keep up with the knowledge explosion.

Being Professionally Inviting With Others

The final dimension of Invitational Theory is being professionally inviting with others. This involves such qualities as treating people, not as labels or groups, but as individuals. It also requires honesty and the ability to accept less-than-perfect behavior of human beings.

In everyday practice, being professionally inviting with others requires careful attention to the policies that are introduced, the programs established, the places created, the processes manifested, and the behaviors exhibited. Among the countless ways that individuals can be professionally inviting with others are to have high aspirations, fight sexism and racism in any form, work cooperatively, behave ethically, provide professional feedback, and maintain an optimistic stance.

Professionals who combine the four dimensions of Invitational Theory into a seamless whole are well on their way to putting the theory into practice. The successful individual is one who balances the four dimensions to sustain energy and enthusiasm for teaching, learning, leading, and living.

Conclusion

This paper has introduced Invitational Theory and presented it as a guiding model for inviting success in one's personal and professional life. It described its foundations of democratic ethos, the perceptual tradition, and self-concept theory. It explained how the elements, domains, levels, and dimensions of functioning work together to encourage human potential.

Increasingly, Invitational Theory is finding its way into health care facilities, educational institutions, management work places, and parenting. Wherever it goes, it carries the basic message that human potential, while not always evident, is always there, waiting to be discovered and invited forth. Invitational Theory offers a concrete, practical, and successful way to accomplish its stated purposes.

References

Jourard, S. M. (1974) The undisclosed self. New York. Mentor Books Mizer, J. E(1964). Cipher in the snow. NEA Journal, pp 8–10.

Novak, J. J, Armstrong, D. E. and Browne, B (2014) Leading for Educational lives: Inviting and sustaining imaginative acts of hope in a connected world. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam/Boston.

Purkey, W. W. Self concept and academic achievement. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Purkey W. W. (1978) Inviting school Success: A self-‐concept approach to teaching and learning. Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont, California.

Purkey, W. W. and Novak, J. M. (1996) Inviting school success: A self-concept approach to teaching, learning, and democratic practice, Third Edition. Wadsworth Publishing. Belmont, California.

Purkey, W. W. and Schmidt, J. J. (1987). The Inviting relationship: An expanded perspective for professional counseling. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Purkey, W. W. and Siegel, B. L. (2013) Becoming an invitational leader: A new approach to professional and personal success. Humanix Press, West Palm Beach, Florida.

Purkey, W. W., Novak, J. M., Fretz, J. (2020). Developing Inviting Schools: A Beneficial Framework for Teaching and Leading, Teachers College Press, New York.

Rogers, C. R. (1969) Freedom to learn. Columbus, Ohio. Charles Merrill.

Photo by Kampus Production from Pexels