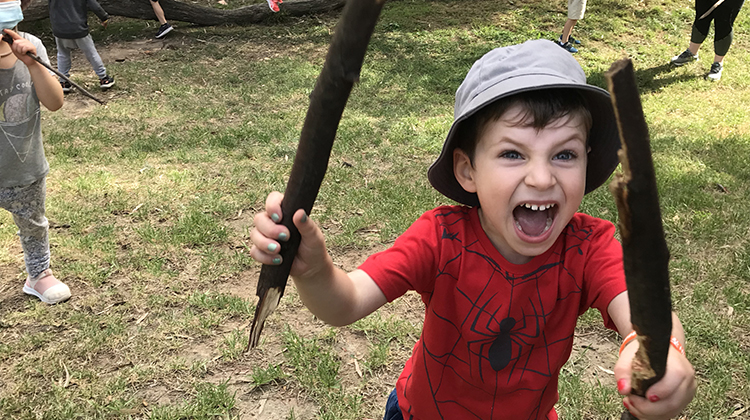

No More Pew Pew Pew!: Looking at Weapon and Superhero Play

As a Kindergarten Teacher, every year I get asked by parents and colleagues on my thoughts and take on managing weapon and superhero play with my kindergarteners when children show a level of aggression through pretend guns, making pretend weapons and assigning roles such as ‘baddies’ and ‘good guys’.

Do you allow it or not? What do you do? Isn’t it bad to allow ‘guns’ in their play?

Everyone from mum, dad, and teachers of different kinder kids will have different opinion on this, as our own personal values will most likely be transmitted to and dictate children’s superhero play. Weapon play from an adult perspective is tainted with what the media portrays constantly; how weapon play is a source of joy and friendship or conflict between children or even siblings (Cupit, 1989).

Before I get to my own verdict about this matter, it is important to take a macro-approach on this and have a second look at what it means when children (whether it is boys or girls) engage in weapon play.

Why Do Children Like Playing with Guns and Shooting People?

Cupit (1989) explains that the superhero (including cartoon characters) is an irresistible wonder to children, because it allows children to be immersed in a world that is exciting compared to their daily experience.

Children often try to replicate the storyline and novelty of special powers through imaginary, dramatic and pretend play – it is exciting without being threatening to a certain extent. Superhero play follows a predictable and easily understood formula, where victory is obtained through who has a higher level of power or violence inflicted on another, and there are always ‘sides’.

What is important to understand here is that superhero play satisfies a learning need in children.

Fantasy: The novelty and breaking out of the day-to-day routine excites children.

Vigorous Exercise: A channel to release tension and stress through the physical aspect of running around and chasing each other as well as being loud.

Social: Cupit (1989) explains how children with language or social difficulties often prefer to be playing in superhero play. This kind of play allows easy participation, quick success and a ‘feel good’ element and it is an easy way to exercise leadership aspects. It can be done cooperatively between different peers or joined spontaneously by running around and screaming together (parallel play). Superhero play is repetitive, simple and is a common interest of many children. It is simple to learn, replicate and initiate. It also acts as an excellent glue for bonding.

How Should I Respond to My Kindergarten Children Playing with Guns?

There are generally two types of responses a teacher may follow (Cupit, 1989; Bauman, 2015):

- Completely banning and zero-tolerance policy. According to Heikkila (2021), in the 2000s, British Kindergartens chose this option and completely ban superhero play from occurring in their kindergarten setting. Banning is the most common response and the least useful according to research (Cupit, 1989).

- Replacing and extending the superhero play. Before teachers aim to replace and extend children’s superhero play, it is important to dedicate regular observation to children’s play.

By gaining a deeper understanding of children’s intentions, we can better equip our response to their weapon play.

Ask yourself (Cupit, 1989; Bauman, 2015):

- What starts the superhero play? What clues can you gather by watching their communication, language and phrases or non-verbal cues?

- Under what scenario does superhero play occur? What environmental factors elicit and minimises it? Think about the amount of space your classroom provides, as well as the types of toys children are allowed to play with.

- What is the pattern of your group of children’s superhero play? What is the trend and normal storyline that they go back to from time to time?

Replacing and extending the superhero play opens a conversation with and genuine understanding in children (Bauman, 2015). We may ask follow-up ‘what if’ questions and extend the learning in the superhero narrative, such as learning about spider webs and their strong adhesiveness in relation to Spiderman. Transformers may flow well into discussions about metamorphosis in animals such as butterflies and frogs (Cupit, 1989).

I am a strong advocate for option number 2 for responding to children’s superhero play. I try to establish limits and rules for superhero play (even wrestling play) with children as a whole group so we can keep everyone engaged and active, while simultaneously listening to their choice.

We have rules such as only a certain number of people can be in one superhero play, when during the day we can play superhero and guns, what toys to use, and that only children who want and say yes to the play can be ‘shot’ or ‘pew pew-ed’. This has been a process to go through; it has been great seeing how children respond to their peers’ socio-emotional needs, but also how they self-regulate their emotions that arises from superhero play (Bauman, 2015).

What if the Play is Too Intense Up to The Point Of “Killing” And “Die Die Die”?

Grimmer (2019) states that when children’s superhero play diverges to the point of killing and dying, educators need to remember that this is still fantasy play. Children are enacting a narrative, not necessarily what they want to happen.

Children do not fully grasp the meaning behind ‘kill’, ‘dead’ and die’ as they only understand one or two sides to death. The concept of death for an adult means there is no coming back (irreversibility), all living things die (universality and inevitability), we grow old (cessation) and causality (something happens to us to cause our death). Children are still understanding the ‘deadness of dead’ throughout their play, hence it is important for adults and educators to take a step back to prevent themselves from putting too much meaning into children’s play. Moreover, engage children in these conversations openly and discuss some ground rules or limits together – replace or extend this learning.

Ultimately, superhero play is not that much different compared to children’s other forms of play, as at the end of the day, it is what it is – play.

Teachers must not be intimidated by the mystique superhero play bears due to what the media portrays (Cupit, 1989). Like any issue, we cannot expect to guide and support it in one go. It takes a process that we have to keep working on. Teachers who are passionate, genuine, and consistent can transform the superhero ‘concerns’ into an educational challenge that in turn reframes the issue into a source of growth experience for both adults and children (Cupit, 1989).

References

Cupit, C.G. (1989). Socialising the superheroes. Australian Early Childhood Resource Booklets, 5 (NBG 2618). Australian Early Childhood Association.

Heikkila, M. (2021). Boys, weapon toys, war play and meaning-making: Prohibiting play in early childhood education settings? Early Child Development and Care, DOI: 10.1080/03004430.2021.1943377

Bauman, J. (2015). Examining how and why children in my transitional kindergarten classroom engage in pretend gunplay. Studying Teacher Education, 11(2), 191-210. DOI: 10.1080/17425964.2015.1045778

Grimmer, T. (2019). Calling all superheroes: Supporting and developing superhero play in the early years. Play in the Early Years, Taylor & Francis Group.