Maximising impact on student learning: high effect size strategies in a science classroom

As an early career teacher, more so than experienced teachers, you are exposed to numerous teaching practices that all work to enable greater student learning. These varying practices are all supported by copious amounts of evidence and all prove to be appealing to a newly graduate teacher. It creates a problem – they can’t all be implemented at once, but how do we know which practices we should be using and which will work best?

What if there was a way to identify which teaching practices would lead to the greatest impact on students’ learning?

In Visible Learning for Science, John Hattie shares his findings from conducting meta-analyses of more than 80,000 studies and 300 million students (Hattie, 2012) to decipher what strategies for delivering learning experiences will have the greatest influence on student learning. Teachers can view each facet of teaching in a new light, uncovering what they should be prioritising in order to maximise student learning and engagement.

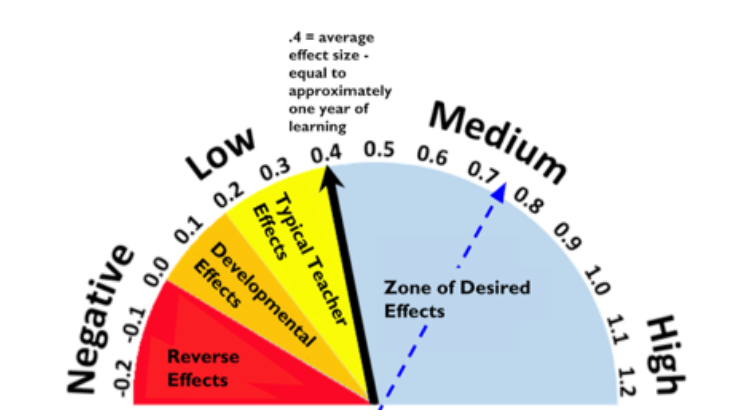

Hattie uses the barometer of effect as a visual representation of the effect size of many strategies and compare them to the potential progress that they can enable students to achieve. The goal is to implement strategies that give every student one years’ worth of growth each school year. “Student growth is a measure of the individual progress a student makes over time along a defined learning progression. Focusing on student growth matters because it enables every student to progress regardless of starting point or capabilities” (Gonski et al. 2018, p. 5)

Using Hattie’s barometer of influence can help teachers implement teaching strategies that adhere to priorities in education that lie outside of the Visible Learning framework.

In their report of the review of Australian schooling to the Australian Government, Gonski et al. (2018) identified the following three priorities that will promote excellent educational outcomes for all school students in Australia:

- Deliver at least one year’s growth in learning for every student every year;

- Equip every student to be a creative, connected and engaged learner in a rapidly changing world; and

- Cultivate an adaptive, innovative and continuously improving education system.

The report identifies issues within the Australian schooling system, outlining that changes come about when we implement a “set of shifts across Australian education systems, and a sustained, long-term and coordinated improvement effort based on shared ambition, action and accountability” (Gonski et al. 2018).

The accumulation of data presented suggests that teachers who are implementing the principles of Visible Learning, will be addressing much of the criteria to establish a significant improvement in the Australian education system.

Many of the teaching practices that feature high in effect size in Visible Learning are strategies that are frequently used in classrooms, albeit unknown to the teacher the extent of the effect they truly have. The focus of this article is to identify some simple strategies that could easily be implemented or may be currently utilised that, with awareness and intention, can easily lead to a large effect on student learning. I will use examples of my own implementation of these practices, including classroom data to demonstrate reflection on my own impact.

Teacher clarity

From the onset, Visible Learning outlines one of the focal strategies teachers can implement to develop a greater learning environment – teacher clarity. Each chapter is introduced with clear and concise success criteria of the content ahead. This allows teachers to reflect on whether their learning environments are as clear. Can your students answer:

- What am I learning today?

- Why am I learning this?

- How will I know that I learned it?

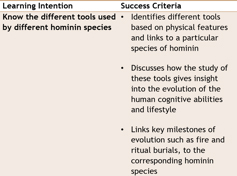

Teacher clarity is directly linked to students being able to take ownership of their learning and self-reflect. If they have clear success criteria, they can measure their own learning progression in a lesson. Starting the lesson with clearly outlined learning intentions and success criteria displayed is one example of achieving teacher clarity as seen in Figure 2, which is an excerpt from one of my own lesson plans. The goal is for teachers to make it very clear to students what they need to know and what they need to be able to do. Hattie cites the meta-study of Frank Fendick, which outlines other contributing factors to teacher clarity, which include:

- Clarity of speech

- Clarity of organisation

- Clarity of explanation

- Clarity of examples and guided practice

Figure 2: Learning intentions and success criteria from a lesson on tool culture (Human Biology).

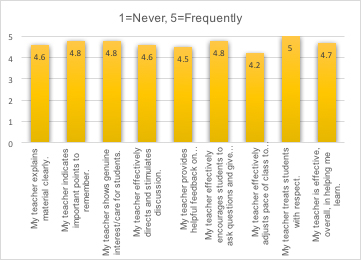

Focus on encompassing teacher clarity is evident when looking at the results from a recent teacher feedback activity conducted by Year 12 students in my Human Biology ATAR class (Figure 3). Using a scale of 1: never, 5: frequently, students responded to prompts such as my teacher explains material clearly and my teacher indicates important points to remember. It is clear that reflective practices and focus on improving practices related to teacher clarity have led to students responding to the prompt my teacher is effective, overall, in helping me learn, with an average of 4.7 out of 5.

Some student comments included:

“Teacher explains the content through various methods such as power points and creative activities which helps me understand it clearly”

“My teacher provides very detailed explanations and explains further when we have questions”

Figure 3: Year 12 Teacher Feedback Results

Teacher credibility

Teacher credibility sits high on the barometer of influence, with an effect size of 0.9, it can lead to considerable growth in the classroom. This sits far higher than some strategies such as practice testing, which sits at 0.54, or cooperative learning at 0.40, with these two practices being so commonly used in classrooms and sought after by students. Teacher credibility encompasses four major components: trust, competence, dynamism and immediacy.

Trust can be defined as a firm belief in the reliability, truth or ability of someone and in a classroom, trust needs to be a two-way relationship. Students should trust in the fact that you care about both their personal and academic achievements. Teachers need to demonstrate trust in students and their capabilities and give them ample opportunities to exercise this trust.

Some practices to build trust in a classroom can include:

- Being consistent with your words

- Building a positive environment in your classroom

- Communicating with transparency

Strongly linked to trust is respect. Hattie (2012) cited the “essence of positive relationships is the student seeing the warmth, feeling the encouragement and the teacher’s high expectations, and knowing that the teacher understands him or her.”

The focus on these practices is evident when looking at the results from a recent teacher feedback activity conducted by my Year 12 Human Biology ATAR students (Figure 3). When responding to the prompt, my teacher shows genuine interest/care for students, some comments included:

“She does show genuine care/interest towards her students and cares about how well we do.”

“She is very caring and it's clear that she is genuinely concerned with how we are going. She also takes an interest in our lives/what we are interested in.”

When responding to the prompt, my teacher treats students with respect, some comments included:

“Yes, this is probably one of her bigger things she does and she definitely expects the same respect back”

“Always treated kindly and with respect. Always feel included and valued in the classroom”

Classroom practices - Jigsaw and mnemonic

In content heavy areas of teaching such as Science, two particular strategies that are positioned very high in the zone of desired effect (Figure 1) are utilising mnemonics and jigsaw activities.

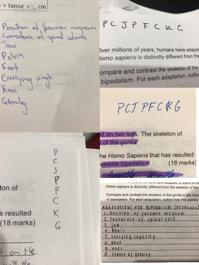

Mnemonics are a tool to help us remember particular sections of information and can be in the form of a rhyme, acronym, phrase or sentence. As a class, my students in Human Biology have created mnemonics to help retain large bodies of information that require a high level of detail on a particular topic. With an effect size 0.76, it is no surprise that this strategy proves to have a large impact on students’ learning. An example of this is presented in Figure 5. Students collectively created a mnemonic for all of the adaptations for bipedalism. This mnemonic then appeared frequently on students test papers as they retrieved the correlating information.

Figure 4: An accumulation of students’ test papers utilising the mnemonic the class collectively made.

Jigsaw activities involve students being assigned to a particular group. Each member of the group is given a section of information regarding a particular topic. In our case, this was a particular disease of a collection of diseases we were studying. Students analyse a section of information independently (one disease), later joining with other students that have also analysed the same information (same disease), forming an expert group. In these expert groups, students decide the key points of information presented in the corresponding information and answer any analytical questions provided by the teacher in order to form a concise summary.

Students return to original groups to share their understanding, teaching their peers about the disease they have become an expert on. The activity results in each student developing an understanding of many diseases, whilst being responsible for their learning and cooperating and communicating effectively with their peers. With an effect size of 1.20, this strategy proves to have a largely positive impact on student learning whilst developing ‘soft skills’ that enable our students to develop into well rounded learners that have effective communication skills and social skills.

Figure 5: Students completing a jigsaw activity

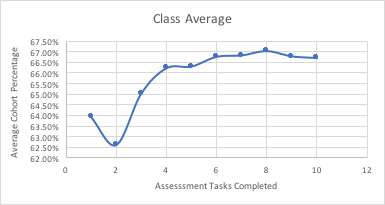

A focus and intentional use of the above-mentioned practices has led to increased student achievement which is evidenced in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Average cohort percentage achieved of assessments completed by Year 12 students

These Visible Learning effects are just a few of the 252 influences Hattie has uncovered. Reflecting on current teaching practices and implementing some of the key, high effect size, learning strategies Hattie presents in Visible Learning will help to move students to a place of progress. Visible Learning for Science challenges teachers to question, what do we want our impact on learning and learners to be? The answer to this lies in challenging our own teaching practices and recognising where we can be more intentional with the strategies we implement in our classroom to achieve the greatest impact on student learning.

References

Doran, M. (2019). Barometer of Influence. [image] Available at: https://www.smore.com/ux92a-social-studies-scoop [Accessed 13 Sep. 2019].

Fendick (1990): The correlation between teacher clarity of communication and student achievement gain (Unpublished Ph.D. University of Florida)

Gonski, D., Arcus, T., Boston, K., Gould, V., Johnson, W., O’Brien, L., Perry, L., & Roberts, M. 2018. Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools. https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/through-growth-achievement-report-review-achieve-educational-excellence-australian

Hattie, J 2009, Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge

Hattie, J 2012, Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximising impact on learning, Routledge, London and New York